Consideration of the proposed hypothesis confronts us with two theories of perceptual learning that represent fairly clear alternatives. This hypothesis ignores other schools and theories and proposes the following questions for solution. Does perception represent a process of addition or a process of discrimination? Is learning an enrichment of previous poor sensations or is it a differentiation of previous vague impressions?

According to the first alternative, we probably learn to perceive in the following way: traces of past influences are added to the sensory basis according to the laws of associations, gradually modifying the perceptual images. The theorist can replace the images in Titchener’s above-mentioned concept with relationships, inferences, hypotheses, etc., but this will only lead to the theory being less

accurate, and the terminology more fashionable. In any case, the correspondence between perception and stimulation gradually decreases. The last point is especially important. Perceptual learning, understood in this way

Thus, it certainly comes down to enriching sensory experience through ideas, assumptions and inferences. The dependence of perception on learning seems to be opposed to the principle

dependence of perception on stimulation. According to the second alternative, we learn

perceive as follows: gradual clarification of qualities, properties and types of movements

leads to changes in images; perceptual experience, even at the beginning, is a reflection of the world, and

not a collection of sensations; the world acquires more and more properties for observation as

how objects appear in it more and more clearly; ultimately, if learning is successful,

phenomenal properties and phenomenal objects begin to correspond physical properties

And physical objects in the surrounding world. In this theory, perception is enriched through discrimination, and

not through the addition of images. The correspondence between perception and stimulation is becoming greater, not less. It is not saturated with images of the past, but becomes more differentiated.

Perceptual learning in this case consists of identifying physical stimulation variables that previously did not elicit a response. This theory especially emphasizes that learning must always be viewed in terms of adaptation, in this case as the establishment of closer contact with environment. It therefore does not explain hallucinations, or illusions, or any deviations from the norm. The last version of the theory should be considered in more detail. Of course, the claim that perceptual development involves differentiation is not new. Gestalt psychologists, especially Koffka and Lewin, have already spoken about this in terms of phenomenal description (although it was unclear how exactly differentiation relates to organization). What is new in this concept is the statement that the development of perception is always an increase in the correspondence between stimulation and perception and that it is strictly regulated by the relationship of the perceiving subject with the environment. The following rule applies here: along with the increase

the number of distinct images increases the number of distinguishable physical objects. An example might

explain this rule. One person, say, can distinguish between sherry, champagne, white wine and red

wine. He has four images in response to all possible types of stimulation. Another person can distinguish

a variety of sherry sorghums, each in numerous varieties and blends, and the same for other wines. He has four thousand images in response to all possible types of stimulation. This example raises an important question: what is the relationship of differential perception to stimulation?

Stimulus is a very slippery term in psychology. Strictly speaking, stimulation is always energy supplied to the receptors, i.e. proximal stimulation. The individual is surrounded by a mass of energy and immersed in its flow. This sea of stimulation consists of displaced invariants, structures and transformations, some of which we know how to isolate and use, others we do not.

The experimenter, conducting a psychological experiment, selects or reproduces some sample of this energy. But it is easier for him to forget this fact and assume that a glass of wine is a stimulus, when in fact it is a complex of radiant and chemical energy that constitutes the stimulus.

When a psychologist speaks of stimuli as signs or carriers of information, he easily omits the question

how stimuli acquire feature function. External energy has no properties

characteristics until differences in it have a correspondingly different effect on

perception. The whole range of physical stimulation is very rich in complex variables, theoretically all of them

can become signs and sources of information.

This is precisely the subject of teaching. All responses to stimulation, including perceptual responses, exhibit some degree of specificity and, conversely, some degree of nonspecificity. A connoisseur exhibits a high degree of specificity of perception, while a layman who does not distinguish between wines exhibits a low degree of specificity. A whole class of chemically different liquids is equivalent to it. He can't tell the difference between claret and Burgundy and Chianti (Italian red wine). His perception is relatively undifferentiated. What did the first individual learn as opposed to the second? Associations? Images of memory? Relationships? Inferences? Did he have perception instead of simple sensations? Possibly, but one can conclude more

simple: he learned to distinguish more types of wines by taste and smell, i.e. a greater number of variables

chemical stimulation. If he is a true expert and not a deceiver, one combination of such variables

may elicit a specific naming or identification response, and a different combination will elicit a different

specific answer. He can accurately use nouns for various liquids of any class and adjectives to describe the differences between them.

Classical theory perceptual learning with its acceptance of the determining role in the subject’s perception of his experience, and not stimulation, is supported by experimental studies of erroneous perception of form, illusions and distortions, facts of individual differences and social influences in perception. It is assumed that the learning process took place in the subject's past experience; it is rarely traced by the experimenter. These experiments do not examine learning because they do not control the exercise process and do not take measurements before and after training. True experiments in perceptual learning always deal with discrimination.

One source of evidence for the discriminative type of learning is studies of features of verbal material. An analysis of such features was made by one of the authors of this article (Gibson, 1940), who, in accordance with the developed point of view, used the terms generalization and stimulus discrimination. This analysis led to a series of experiments concerning what we call identification responses. We assume that motor responses, verbal responses, or images are identification responses if they specifically correspond to a set of objects or phenomena. Learning to code (Keller, 1943), recognizing types of airplanes (Gibson, 1947), and recognizing the faces of one's friends are all examples of increasing specific correspondence between individual stimuli and responses. When this answer begins to be persistently repeated, they say that the image has acquired the character of familiarity, recognition, and meaningfulness.

There is another theory that is completely opposite to the above and is, as it were, its antithesis. Its followers argue that modern international law does not provide for the payment of any compensation to foreign owners, especially when it comes to nationalization carried out as part of a broad program of socio-economic reforms, and when no compensation is paid to national owners who have been expropriated no compensation.

This theory, however, does not find any sympathy or support from states in the practical activities. Experience, in particular the experience of numerous nationalizations since the Second World War, shows that foreign owners are almost without exception given some compensation, although sometimes this is paid only after many years and often as part of global compensation agreements between the state that carried out the nationalization and the state whose citizens suffered during its implementation. Even socialist states, whose economic policy is based on the state monopoly on the means of production, presented and satisfied inter se demands for compensation for damage caused to their citizens as a result of the nationalization of their property 1o1 carried out by other socialist countries. Thus, the practice

This evidence suggests that the legal justification for paying compensation in the event of nationalization should not be sought in the classical doctrine of acquired property rights protected in international order, but in some other legal principles.

The legal basis for the actual behavior of states, which unites and brings together both of these doctrines, is the general legal principle prohibiting unjust enrichment 102.

If a state that nationalizes the property of foreigners does not provide them with any compensation, it unjustly enriches itself at the expense of another state, which is a completely independent political and socio-economic unit. Exercising its sovereign right to nationalization, the state at the same time deprives another state of its wealth, consisting of capital placed abroad, taking advantage of the fact that the latter’s material resources were imported into its territory and came under its jurisdiction.

In accordance with this principle, first of all, one should take into account not the financial losses and various types of losses incurred by any specific foreign owner who was subjected to expropriation, but the enrichment, income and profits received by the state that carried out the nationalization. It is the actions that caused the transfer of property in favor of the state or its representatives that entail the obligation to provide compensation. If, for example, the state, for political reasons, completely liquidates any industrial or commercial enterprise, the activities of which cause harmful or dangerous consequences for human health, it is obliged to pay compensation. The fact is that in such cases the state carrying out nationalization does not receive any material benefit, even if the foreign owner suffers any losses. Likewise, the loss of clientele or “key” positions in the field economic activity Not

may provide grounds for compensation if the abolition of freedom of competition negates the potential benefits of that intangible advantage.

However, the principle of domestic law prohibiting unjust enrichment should not be transferred mechanically and in all its aspects to the sphere of international law.

These rules of domestic law should be regarded rather as “one of the indicators of policy and principles” 103. The principle of unjust enrichment has such great importance in application to nationalization, mainly due to the fact that it is based on the equality of the parties and obliges us to take into account in each specific case all the circumstances of the case, comparing the claims of the foreigner who was subjected to expropriation and the benefits that he could illegally receive before nationalization.

The fact is that the principle prohibiting unjust enrichment operates in both directions, that is, it can be applied both in favor of the foreigner whose property has been paciopalized and against him. This suggests that the amounts of profits illegally obtained by foreign owners during periods when they had a monopoly over their activities or occupied privileged economic positions, such as during the colonial era, can be calculated and then deducted when paying compensation.

Provisions of the Charter of Economic Rights and Duties of States relating to nationalization

In paragraph “c” of paragraph 2 of Art. Article 2 of the Charter of Economic Rights and Responsibilities of States declares that every state has the right “to nationalize, expropriate or transfer foreign property. In this case, the State taking such measures must pay appropriate compensation, taking into account its relevant laws and regulations and all circumstances that that State considers relevant. In any case where the question of compensation is in dispute, it must be settled in accordance with the internal law of the nationalizing State and its courts,

unless all interested States voluntarily and by mutual consent reach an agreement regarding the search for other peaceful means of settlement on the basis of the sovereign equality of States and in accordance with the principle of free choice of means.”

The question arises as to which of the various points of view regarding the payment of compensation was taken as the basis for the preparation of this article.

It is clear that this is not the traditional doctrine of "just or adequate, prompt and effective" compensation. At the initial stage of preparation of the text of the Charter of Economic Rights and Responsibilities of States, industrialized countries insisted that these were the requirements of international law and made a proposal to that effect. 104 The vast majority of states rejected this proposal, thereby demonstrating that this supposed customary rule does not have the necessary universality and uniformity i05. Thus, in the process of developing the provisions of the charter, it was convincingly proven that the traditional doctrine does not reflect the general consensus of states on this issue and, therefore, cannot be considered as a valid norm of customary international law |06.

The preparatory materials of the Charter of Economic Rights and Duties of States also indicate that this article is not based on a theory that generally rejects the need to pay any compensation. II, although at first the Working Group for the preparation of the text of the charter took exactly this position, during further discussion it abandoned this point of view. In the original version of the article, about

106 For the same reason, the argumentation of Prof. Dushop, given in one of the arbitration awards. According to him, the objection of the 10 most industrially developed countries to the wording of this article suggests that the general consensus on the problem is still expressed in Resolution 1803, adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1962 and interpreted in a sense that confirms the traditional thesis. The disagreement of 110 developing states with this thesis completely refutes the idea of an alleged consensus derived from resolution 1803, interpreted in a very specific way.

107. It is clear that such wording did not impose a strict obligation to provide compensation and left the issue of its payment to the discretion of the nationalizing state. Only a few days before the final vote, the Group of 77 reconsidered its position and included in the text of the charter a provision obliging the payment of “appropriate compensation.” 108 This provision transformed the problem of payment of compensation “from some vague possibility into a completely concrete principle.” 109 Finally The approved text of the charter not only obliges the payment of “appropriate compensation”, but also establishes that the question of its payment will be decided “having regard to ... all the circumstances which this state considers appropriate.”

In the process of developing the Charter of Economic Rights and the responsibilities of states, some useful recommendations regarding exactly what circumstances should be considered relevant when deciding on the payment of compensation. One may be the length of time that the expropriated enterprise has been exploiting local resources, another may be whether it has recouped its original investment, whether there has been unjust enrichment as a result of exploiting the opportunities offered by colonial rule, or whether profits have been made. too high. The contribution of the nationalized enterprise to the socio-economic development of the country, compliance with labor legislation, its reinvestment policy, etc. Tax debt in itself is not a factor influencing the amount of compensation provided, but it can be considered a kind of loan received from the state, which can be repaid at the time of payment of compensation.

It is for these reasons that the Charter of Economic Rights and Duties of States, defining the nature of the

pensatspn, uses the term “appropriate” instead of “fair” or “adequate”. The first clause of these adjectives much better expresses the whole variety of circumstances that may be considered appropriate in each specific case.

The main features of this article - recognition of the payment of compensation as an international obligation, determination of its volume taking into account all the circumstances of the case and the need to maintain equality of rights of the parties - clearly indicate that this provision of the Charter is based on the principle prohibiting unjust enrichment. The concept of “appropriate compensation” is quite flexible and, when deciding on the payment of compensation, allows taking into account all the elements relating to the formation and subsequent activities of a foreign enterprise in order, taking into account the specific circumstances of the case, to prevent one of the interested parties from using the opportunity for unjust enrichment.

Criticism of the provisions of the Charter of Economic Rights and Duties of States relating to nationalization

However, this interpretation of this provision of the Charter of Economic Rights and Duties of States is not predominant, especially among authors from industrialized countries. Most often, these authors criticize paragraph “c” of paragraph 2 of Art. 2 of the Charter for the fact that the letter “does not even mention the possibility of applying international law in the settlement of issues relating to foreign investment” "". This qualifies as a “complete refusal to use international law” in the implementation of measures for the expropriation of foreign property 112. The Charter is interpreted as a document declaring exclusive jurisdiction

110 C a s I a ii with d a J. Justice econoniiquc inlornalionale. - In: "Contribution a l"Etudc de la Cbarte", ed. Gallimnrd. p. 105.

111 Statement by the Delegate of Canada (U.N. Doc. L/S. 2/SR. 1.640. 1974).

of a nationally punishing state, and “internal law, understood in this way, allows that state to use all available means to avoid fulfilling the established obligation” w. Other critics point out that the only obligation imposed by the charter is “to provide compensation, if any, which can be judged as appropriate only from a subjective point of view, taking into account only the provisions of domestic law and local circumstances in relation to which the norms of international law are inapplicable” I4. It should be recognized that the wording of paragraph “c” of paragraph 2 of Art. 2, which was the result of a compromise reconciling different points of view II reached at the very last moment, is indeed so vague and ambiguous that such an interpretation suggests itself. However, an analysis of this entire regulation in its context and taking into account other sections of the charter, which should be considered as a whole (Article 33, paragraph 2), as well as studying it in the light general principles international law lead, in our opinion, to a completely different interpretation.

Indeed, paragraph “c” of paragraph 2 of Art. 2 of the Charter of Economic Rights and Responsibilities of States, unlike UN General Assembly Resolution 1803 of 1962, does not contain a provision establishing that in the event of nationalization or expropriation, appropriate compensation shall be paid to the foreign owner “according to the rules in force in the state that takes these measures in the exercise of its sovereignty and in accordance with international law.” The removal of this phrase from the text of the charter is mainly due to the insistence with which industrialized states have argued that customary international law establishes an obligation to pay “just, prompt and effective” compensation. This formulation of the question aroused unease among the “third world” countries.

414 In rower and T e r e. The Charter of Economic Rights ana Duties of States: A Reflection or a rejection of International Lav. - “9 International Lawyer*), 1975, p. 305.

trust and “suspicion as to who exactly is keeping Western countries away from international law” and5.

But when it became obvious that the principle of “fair, prompt and effective” compensation no longer found support among the overwhelming majority of members of the international community, the reference of industrialized states to this actually non-existent norm of general international law lost all meaning. The mere mention of international law or the absence thereof does not change the essence of the question of what is the main meaning of international legal norms on the issue under consideration. Right. also what the Charter of Economic Rights and Responsibilities of States says about the expropriating state applying its laws and regulations and taking into account all circumstances that it considers relevant. The implementation of such actions at the initial stage is completely natural, since in accordance with the rule on the need for preliminary exhaustion of internal possibilities, national law, like other local remedies, must be used first. And even after this, the state that carried out the nationalization is still obliged in accordance with paragraph “c” of paragraph 2 of Art. 2 charters to pay “appropriate” compensation.

Thus, if the expropriating state, in the application of its laws and s. taking into account its own assessment circumstances will offer compensation that another state (but not the individual or injured company) does not consider appropriate, the subjective decision of the nationalizing state is not final and does not mean the termination of the case. The State whose nationality is the owner of the expropriated property may, in accordance with international law, take it under its protection and bring a claim on its behalf, based on the fact that the international obligation provided for in the Charter itself to pay “appropriate compensation” has not been fulfilled. In this case, an international dispute arises between the two states, as noted in the charter provision in question.

115 Do Waart. Permanent Sovereignty over Natural Resources as a cornerstone for International Economic Rights and Duties. - “24 Netherlands International Law Reviews, 1977, p. 313.

Industrially developed countries have proposed that international disputes arising as a result of measures taken for nationalization or expropriation, after exhaustion of internal possibilities, must be referred to judicial or arbitration proceedings. The Group of 77 did not deny the existence of a dispute in such cases, but believed, however, that disputes about foreign investment should be considered in exactly the same manner as other international disputes of a legal nature. Although in paragraph 3 of Art. 36 of the Charter of the United Nations and establishes that disputes of a legal nature should “as a general rule be submitted by the parties to International Court", in practice, another system prevails, which corresponds to the principle of free choice of means of peaceful settlement of disputes proclaimed in UN General Assembly resolution 2625, which provides that no state is obliged to accept any particular method of peaceful resolution controversial issues except with your express consent.

The theory of "job enrichment" is based on the assumption that workers should have a personal interest in doing a particular job. "Work enrichment" is aimed at structuring labor activity in such a way as to give the performer the opportunity to feel the complexity and significance of the task entrusted to him, autonomy and independence in choosing decisions, the absence of monotonous work, and responsibility for the implementation of the task.

Today, many enterprises use the theory of “labor enrichment” to eliminate the negative consequences of fatigue and the associated drop in labor productivity.

At the same time, in practical activities some shortcomings of Herzberg’s theory should be taken into account. In particular, as research shows, assumptions about the existence of a strong correlation between job satisfaction and labor productivity are not always justified. For example, communication with colleagues helps to satisfy the employee’s social needs. However, the same employee may consider communication with colleagues more important matter than doing the work assigned to him. Thus, despite a high degree of job satisfaction, labor productivity may not be high enough. Considering the fact that social needs play a very important role, the introduction of such motivating factors as increased responsibility for the assigned task may not have a motivating effect and may not contribute to increasing labor productivity. Therefore, motivation must be perceived to a certain extent as a probabilistic process. What motivates of this employee in a particular situation may not have any effect on him at another time. This circumstance must be taken into account when addressing specific issues of personnel management.

The interaction of motives is as follows: if an employee makes the goals of the organization his personal goals (identification), then the fulfillment of his production tasks at the same time causes personal satisfaction. Personal satisfaction in turn contributes to achieving higher results. Motivation within groups or areas of an enterprise creates the conditions for a sense of collectivism among employees.

The considered substantive theories of motivation are based on the needs that determine employee behavior. In addition to substantive developments, there are procedural theories that give motivation a slightly different direction. In particular, according to these theories, a person’s behavior is not only determined by needs, but is simultaneously a function of his perceptions and expectations, the possible consequences of his chosen type of behavior.

For correct analysis production activities first of all, it is necessary to distinguish between his ability and readiness to work. It should be taken into account that both components are closely interconnected and interdependent. This approach requires careful consideration various factors, which determine the ability and desire to work, since they decisively determine the degree of labor efficiency. Human skill is aimed at developing labor skills, including acquired knowledge, mental and physical capabilities for their application, as well as such specific qualities inherent to the individual as prudence, restraint, patience, sensitivity, and the ability to adequately respond to a situation. This also includes an accurate understanding of the production process and the progress of the work being performed. In other words, each employee must understand well what knowledge and abilities he must have in order to successfully solve the task, and what working conditions are necessary for this.

The concept of perceptual actions, stages of their formation. Theories of perceptual learning (enrichment and differentiation).

The role of motor activity in the development of perception.(according to Gusev “Sensation and Perception”)

We are talking not only about the movement of the eyes, which, as shown by the studies of A.L. Yarbus, Yu.B. Gippenreiter, V.P. Zinchenko, by analogy with the sense of touch, seem to feel an object. As J. Gibson emphasized, “the eye is only part of a paired organ, one of two movable eyes located on the head, which can rotate while remaining integral part body, which in turn can move from place to place.” It was the hierarchy of these organs, the movement of which is directed by the cognitive activity of the subject, that the classics called a functional organ (A.A. Ukhtomsky), a perceptive system (J. Gibson), a perceptive functional system (A.N. Leontyev). N.A. Bernshtein, one of the founders of the Russian physiology of activity, especially emphasized the role of motor activity in the development of perception: “During ontogenesis, each collision of an individual with the outside world, which poses a motor task requiring solution for the individual, contributes to the development in its nervous system of more and more a true and accurate objective reflection of the external world both in the perception and understanding of the situation prompting action, and in the design and control of the implementation of action adequate to this situation.”

The role of active palpating movements in haptic perception is also obvious and well studied. Tactile perception of the shape of an invisible object, in principle, is a process of continuous movement of the probing hand along its surface and the assimilation of the nature of these movements to the shape of the perceived object.

Despite the obviousness of the role of movements in visual and tactile perception, it should be especially emphasized that the motor component of the perceptual process is not just some parallel process of movement of the sense organs or parts of the human body, it is an indispensable condition for the formation and functioning of the visual image. For a more acute fixation of this fundamental problem, following A.N. Leontiev, we emphasize: as mental phenomena, sensations and perceptions are impossible in the absence of movements.

Proving the universality of this principle, A.N. Leontiev, together with his students Yu.B. Gippenreiter and O.V. Ovchinnikova, conducted an original experimental study of the role of the motor component in the formation of pitch hearing, which led to the formulation of the assimilation hypothesis, which is very important for understanding the basic mechanisms of perception : the process of perception is a process of assimilation of the dynamics of the process itself to the properties of an external stimulus. The likeness is expressed in the form of real movement, which is an integral part of the perceptual process.

The research began with observation of Vietnamese students studying at the Faculty of Psychology of Moscow State University. M.V. Lomonosov. Among them there was no one who could be called “musically deaf,” i.e. had low pitch discrimination sensitivity, whereas among Europeans “musical deafness” is a common phenomenon. The fact is that the Vietnamese language belongs to the group of so-called tonal languages, where the semantic structure of speech is conveyed by subtle differences in the frequency of the fundamental tone of speech. In other words, the Vietnamese can intonate perfectly. Thus, the idea arose that in such a “non-motor” modality as hearing, the function of the motor component of the perceptual process is performed by the vocal apparatus.

Experiments were conducted to develop sensitivity to distinguishing the pitch of vowel sounds (“o”, “i”, “e”). These sounds were recorded on a tape recorder at different frequencies of singing by a professional singer. Pitch-deaf subjects1 took part in the experiments as subjects, i.e. those who were very poor at distinguishing the differences in pitch between the sounds used.

In the first series of experiments, differences in sound-pitch sensitivity were measured. Next, the subjects were taught correct intonation, ensuring that each sound was sung correctly. The subject had to adjust his voice to a given pitch, receiving information on a special indicator about the correspondence between the pitch of his voice and the voice of the reference sound sung by the singer.

The training took place over 10-15 days, totaling about 30 minutes of pure time. In the second series, the thresholds of sound-pitch sensitivity were measured again. A significant decrease in thresholds was found, i.e. The subjects became very sensitive to tonal differences between vowel sounds. In fact, pitch deafness was eliminated through the development of the motor component of the perceptual function: the practice of intonation was used as a means of assimilating the movements of the vocal apparatus to the dynamics of sound.

Further experimental research was aimed at finding out how this motor element of perception is structured, i.e. how the process of assimilation can be carried out in the emerging perceptual functional system. The idea was to completely remove the ear from this functional system as a sound-sensitive device. The ear was replaced with the surface of the skin of the hand, against which an electromagnetic vibrator2 was placed, transmitting the same range of vibrations to the finger, but no longer sound, but tactile. Thus, hearing was replaced by mechanical vibration sensitivity.

As in previous experiments, the subjects were measured for differential vibrotactile sensitivity, and then they were taught intonation by singing vowels. The result was similar: there was an increase in sensitivity to changes in vibration frequency. Thus, a new functional system was built, where the touch sensor was replaced

1 They, for example, at any height of the fundamental tone of the vowel sound, assessed the sound “u” as lower than “i”, although the actual height of the first sound was higher than the second.

2 The vibrator worked so quietly that the subjects could not hear the sounds it generated, but only felt the vibration. link (sound receptors were replaced by tactile ones), but the motor one remained the same.

In the third series of studies, the transformation of the functional perceptual system was continued: the auditory link was left, but its motor component was changed. The motor skills of the vocal apparatus were replaced by the motor skills of the hand: the subject did not sing vowels, but, while listening to the test recording, pressed the pressure sensor, which linearly converted the pressure into the pitch of the sound, displayed by the same feedback indicator (i.e., the higher the audible sound, the press the load cell plate harder). Thus, a new motor link was created: the movement of the hand was likened to a change in pitch.

The result remained the same - the sensitivity of the pitch-deaf subjects increased. Moreover, this was not an increase of 5-10%, bordering on the level of statistical significance, but different for different subjects - 50, 100, 150, 200%.

These brilliant results show that the development of perception depends on the inclusion of the motor component, which in the situation of an already formed functional system is hidden from direct observation; the process of assimilation is curtailed and internalized. And only in a specially organized formative experiment, simulating the process of individual development of perception, can we see the inclusion of all links of this complex system.

Unfortunately, practical applications of the assimilation hypothesis have not yet been developed in specific training methods for the development of human sensory and perceptual abilities.

Interesting experimental results, in our opinion, well explained by the assimilation hypothesis, were obtained by our fellow psychophysicists M. Pavlova and A. Sokolov when studying sensitivity to biological movement in children suffering from cerebral palsy. The authors examined motion perception thresholds—simulating the movement of human contours using luminous dots—in healthy children and children with cerebral palsy. In children with cerebral palsy, sensory sensitivity was significantly lower. However, after complex therapy, when the quality of the child’s movements was significantly restored, an increase in sensory sensitivity to biological movement was also observed. Thus, apparently, with the normal motor development of a child, motor patterns are formed, which are likened to the models of a walking person visible on the monitor screen.

In the context of the problem under discussion about the fundamental role of motor activity in the development of perception, let us once again turn to the experiments of R. Held and A. Hein with kittens described above: normal visual perception was formed only in the kitten moving in the light, the other remained blind. Apparently, even with the possibility of moving its eyes and head, the kitten sitting in the basket had not formed some basic scheme for displaying those changes in the surrounding space that occur when it moved, in the dynamics of its own movements. It can be assumed that such a scheme is necessary for a very rough assimilation of the optical transformations of the proximal stimulus that arise when moving one’s own body in space to its movements. But even this crude comparison did not happen.

To a certain extent, an extreme case that proves the extreme necessity of eye movement for normal functioning visual perception is an artificial laboratory phenomenon called stabilized retinal image. This experimental technique consists of using a special suction cup or contact lens, attached to the cornea of the eye, a certain test image is supplied to the retina from a miniature indicator (Fig. 131). Because this optical system makes movements together with the eye, then the projection of the test object is motionless relative to the retina. More modern technical means allow image stabilization using special video camera, tracking the movements of the eye and the television monitor, the image on which is shiftedis displayed according to the decoded signals coming from the camcorder.

Numerous studies have shown that after 1-3 s, the image of the projected image begins to gradually, in parts, fade away, disappear, and the subject sees an unstructured gray field, and a little later it becomes completely black. The results of the experiments established that such a simple figure as a line quickly disappears and then can appear again, while a complex image is perceived in whole or in part much longer. Subjects report that they learn to look at an object without moving their eyes, but by moving their attention along it from one point to another, i.e. performing internal meaningful activity of scanning a complex object. Thus, R. Pritchard's data showed that a single line is seen by the subject only during 10% of the time of its exposure, and a complex object (a profile drawing of a woman's head or a word from which new words can be formed) can be fully or partially preserved up to 80% of the entire time .

Similar results were obtained in the experiments of V.P. Zinchenko and N.Yu. Vergiles.

Thus, experiments with a stabilized image on the retina confirm the thesis that without natural eye movements, the normal construction of a normal visual image is impossible. In the case of internal scanning of a stabilized image by the directed attention of the subject, this image appears to be likened to the movement of this “ray” of attention.

J.J. Gibson, E. J. Gibson

PERCEPTUAL LEARNING - DIFFERENTIATION OR ENRICHMENT? (V.V. Petukhov “Man” as a subject of knowledge", texts, volume III)

The term "perceptual learning" is understood differently by psychologists. Some believe that human perception is largely the result of learning: we learn, for example, to perceive depth, or shape, or meaningful objects. In this case, the main question of the theory is: what part of perception is a product of learning? It corresponds to the debate between nativism and empiricism. Other psychologists believe that human learning depends wholly or partly on perception, expectation, or insight, and that learning is a central cognitive process rather than a motor activity. In the second case, the main question of the theory is: should a person’s perception be studied before his behavior, actions, and reactions are understood? It corresponds to a long-standing debate initiated by an outdated version of behaviorism.

These two trends are far from the same thing, and both problems should be separated from each other. To discuss the role of learning in perception, we need to consider perception and how it is influenced by past experience or practice. To address the role of perception in learning, we need to consider behavior and whether a particular action can be learned through perception or whether it can only be learned through performing that action. This raises two questions:

a) how do we learn to perceive? b) what is the role of perception in the learning process? Both questions are important for solving practical problems of teaching and training, but in this work only the first of them will be considered.

How do we learn to perceive? This question has roots in philosophy and was debated long before the advent of experimental psychology. The question arises: does all knowledge (the modern term is information) come to us through the senses - or is some of it brought in by the mind itself? Sensory psychology has been unable to explain how all the information we have can come through receptors. Therefore, a theory was needed

explanatory addition to perception. There have been many such theories since the time of John Locke. According to the old point of view, addition to perception can only be drawn from rational abilities (rationalism). According to another point of view, it can be derived from innate ideas (nativism). Currently, there are few followers of these theories left. The most popular theory, which has been around for many years, believes that this addition to sensation is the result of learning and past experience. Its modern formula is that our brain accumulates information - perhaps in the form of traces or memory images, and perhaps in the form of relationships, mental attitudes, general ideas, concepts. This approach is called empiricism. According to him, all knowledge comes from experience, and past experience is somehow connected to the present. In other words, experience accumulates, and traces of the past somehow participate in our perception of the present. Helmholtz's theory of unconscious inferences was one of the culminating points of empiricism. It suggests that we learn, for example, to perceive depth by interpreting the sign of color - a sensation that itself lacks depth. Another was Titchener's theory, according to which we learn to perceive an object by attaching, by association, to the sensory core of memory images (context).

More than 30 years ago, this line of thinking was opposed by the theory of sensory

organizations. It was supposed to provide a different explanation for the discrepancy between sensory input and the final image. The Gestaltists subjected the idea of acquired connections between sensory elements and their traces to scathing criticism. Using favorite examples of the perception of visual forms,

they argued that these connections are innate or that they arise spontaneously. They believed that perception and knowledge are organized into structures.

The theory of sensory organization or cognitive structures, although it gave rise to many experiments in a new direction, did not outlive the theory of association after 30 years. Old school of empirical thinking! has begun to recover from critical attacks, and there are signs of a revival in the United States. Brunswick from the very beginning followed the direction founded by Helmholtz;

Ames, Cantril and other followers proclaimed the beginning of neo-empiricism

Other psychologists strive for a theoretical synthesis that incorporates the lessons of Gestaltism while preserving the idea of what we learn to perceive. This direction was led by Tolman, Bartlett and Woodworth. Leeper followed it as early as 1953. Bruner A951) and Postman A951) have recently made an energetic attempt to reconcile the principle of sensory organization with the principle of the determining role of past experience. Hilgard also seems to agree with the organizing process being driven by

relative structure, and with the process of association governed by the classical laws of A951). Hebb has recently made an attempt to systematically and thoroughly combine the best of Gestalt theory and physiological learning theory A949). Almost all of these theorists argue that

the process of organizing and the process of learning are ultimately compatible, that both

the explanations are valid in their own way, and there is no point in continuing the old debate whether learning is the result of organization or organization is the result of learning. The experiments were inconclusive, and the controversy itself was inconclusive. So while they're arguing, the best solution will agree with both sides.

We believe that all existing theories of perception - both the theory of associations, and the theory of organization, and theories that are a mixture of the first two (taking into account attitudes, habits, assumptions, hypotheses, expectations, images or inferences) - have at least one thing in common

trait: they take for granted the discrepancy between sensory input and

ultimately and try to explain it. They believe that we somehow receive more information about the environment than can be transmitted through receptors. In other words, they

insist on the distinction between sensation and perception. The development of perception must therefore necessarily involve addition, interpretation or organization.

Let's consider the possibility of abandoning this assumption altogether. Let's say it's ok

experiment that the input stimulus contains everything that is in the image. What if the stream of stimulation arriving at the receptors gives us all necessary information about the outside world?

Perhaps we acquire all knowledge through our senses, even in a more simplified form than John Locke could have imagined, namely through variations and shades of energy that should be called stimuli.

Enrichment theory and specificity theory

Consideration of the proposed hypothesis confronts us with two theories of perceptual learning that represent fairly clear alternatives. This hypothesis ignores other schools and theories and proposes the following questions for solution. Does perception represent a process of addition or a process of discrimination? Is learning an enrichment of previous poor sensations or is it a differentiation of previous vague impressions?

According to the first alternative, we probably learn to perceive in the following way: traces of past influences are added to the sensory basis according to the laws of associations, gradually modifying the perceptual images. The theorist can replace the images in Titchener’s above-mentioned concept with relationships, inferences, hypotheses, etc., but this will only lead to the theory being less

accurate, and the terminology more fashionable. In any case, the correspondence between perception and stimulation gradually decreases. The last point is especially important. Perceptual learning, understood in this way

Thus, it certainly comes down to enriching sensory experience through ideas, assumptions and inferences. The dependence of perception on learning seems to be opposed to the principle

dependence of perception on stimulation. According to the second alternative, we learn

perceive as follows: gradual clarification of qualities, properties and types of movements

leads to changes in images; perceptual experience, even at the beginning, is a reflection of the world, and

not a collection of sensations; the world acquires more and more properties for observation as

how objects appear in it more and more clearly; ultimately, if learning is successful,

phenomenal properties and phenomenal objects begin to correspond to physical properties

and physical objects in the surrounding world. In this theory, perception is enriched through discrimination, and

not through the addition of images. The correspondence between perception and stimulation is becoming greater, not less. It is not saturated with images of the past, but becomes more differentiated.

Perceptual learning in this case consists of identifying physical stimulation variables that previously did not elicit a response. This theory especially emphasizes that learning must always be viewed in terms of adaptation, in this case as the establishment of closer contact with the environment. It therefore does not explain hallucinations, or illusions, or any deviations from the norm. The last version of the theory should be considered in more detail. Of course, the claim that perceptual development involves differentiation is not new. Gestalt psychologists, especially Koffka and Lewin, have already spoken about this in terms of phenomenal description (although it was unclear how exactly differentiation relates to organization). What is new in this concept is the assertion that the development of perception is always an increase in the correspondence between stimulation and perception and that it is strictly regulated by the relationship of the perceiving subject with the environment. The following rule applies here: along with the increase

the number of distinct images increases the number of distinguishable physical objects. An example might

explain this rule. One person, say, can distinguish between sherry, champagne, white wine and red

wine. He has four images in response to all possible types of stimulation. Another person can distinguish

a variety of sherry sorghums, each in numerous varieties and blends, and the same for other wines. He has four thousand images in response to all possible types of stimulation. This example raises an important question: what is the relationship of differential perception to stimulation?

Stimulus is a very slippery term in psychology. Strictly speaking, stimulation is always energy supplied to the receptors, i.e. proximal stimulation. The individual is surrounded by a mass of energy and immersed in its flow. This sea of stimulation consists of displaced invariants, structures and transformations, some of which we know how to isolate and use, others we do not.

The experimenter, conducting a psychological experiment, selects or reproduces some sample of this energy. But it is easier for him to forget this fact and assume that a glass of wine is a stimulus, when in fact it is a complex of radiant and chemical energy that constitutes the stimulus.

When a psychologist speaks of stimuli as signs or carriers of information, he easily omits the question

how stimuli acquire feature function. External energy has no properties

characteristics until differences in it have a correspondingly different effect on

perception. The whole range of physical stimulation is very rich in complex variables, theoretically all of them

can become signs and sources of information.

This is precisely the subject of teaching. All responses to stimulation, including perceptual responses, exhibit some degree of specificity and, conversely, some degree of nonspecificity. A connoisseur exhibits a high degree of specificity of perception, while a layman who does not distinguish between wines exhibits a low degree of specificity. A whole class of chemically different liquids is equivalent to it. He can't tell the difference between claret and Burgundy and Chianti (Italian red wine). His perception is relatively undifferentiated. What did the first individual learn as opposed to the second? Associations? Images of memory? Relationships? Inferences? Did he have perception instead of simple sensations? Possibly, but one can conclude more

simple: he learned to distinguish more types of wines by taste and smell, i.e. a greater number of variables

chemical stimulation. If he is a true expert and not a deceiver, one combination of such variables

may elicit a specific naming or identification response, and a different combination will elicit a different

specific answer. He can accurately use nouns for various liquids of any class and adjectives to describe the differences between them.

The classical theory of perceptual learning, with its acceptance of the determining role in the subject's perception of his experience, and not stimulation, is supported by experimental studies of erroneous perception of form, illusions and distortions, facts of individual differences and social influences in perception. It is assumed that the learning process took place in the subject's past experience; it is rarely traced by the experimenter. These experiments do not examine learning because they do not control the exercise process and do not take measurements before and after training. True experiments in perceptual learning always deal with discrimination.

One source of evidence for the discriminative type of learning is studies of features of verbal material. An analysis of such features was made by one of the authors of this article (Gibson, 1940), who, in accordance with the developed point of view, used the terms generalization and stimulus discrimination. This analysis led to a series of experiments concerning what we call identification responses. We assume that motor responses, verbal responses, or images are identification responses if they specifically correspond to a set of objects or phenomena. Learning to code (Keller, 1943), recognizing types of airplanes (Gibson, 1947), and recognizing the faces of one's friends are all examples of increasing specific correspondence between individual stimuli and responses. When this answer begins to be persistently repeated, they say that the image has acquired the character of familiarity, recognition, and meaningfulness.

A. V. Zaporozhets

DEVELOPMENT OF PERCEPTION AND ACTIVITY ( V.V. Petukhov “Man as a subject of knowledge”, texts, volume III)

Perception, while guiding the practical activity of the subject, at the same time depends in its

development from the conditions and nature of this activity. That is why in the study of the genesis, structure and function of perceptual processes, the “craxeological”, as J. Piaget puts it, approach to the problem becomes important. The relationship between perception and activity was actually ignored in psychology for a long time and either perception was studied outside of practical activity (various directions of subjective mentalistic psychology), or activity was considered independently of perception (strict behaviorists). Only in recent decades have genetic and functional connections between them become the subject of psychological research. Based on the well-known philosophical principles of dialectical materialism regarding the role of practice in understanding the surrounding reality, Soviet psychologists (B.G. Ananyev, P.Ya. Galperin,

A.N. Leontiev, A.R. Luria, B.M. Teplov, etc.) in the early 30s began to study the dependence of perception on the nature of the subject’s activity. The ontogenetic study of perception, carried out by us together with collaborators at the Institute of Psychology and the Institute of Preschool Education of the APN, also went in this direction.

Features of a child’s practical activity and its age-related changes have

apparently, a significant influence on the ontogeny of human perception. The development of both activity as a whole and the perceptual processes included in it does not occur spontaneously. It is determined by the conditions of life and learning, during which, as L.S. Vygotsky rightly pointed out, the child learns the social experience accumulated by previous generations. In particular, specifically human sensory learning involves not only the adaptation of perceptual processes to individual conditions of existence, but also the assimilation of systems of sensory standards developed by society (which include, for example, the generally accepted scale of musical sounds,

phoneme lattices of various languages, systems of geometric shapes, etc.). An individual uses learned standards to examine a perceived object and evaluate its properties. Standards of this kind become operational units of perception and mediate the child’s perceptual actions, just as his practical activity is mediated by a tool, and his mental activity by the word.

According to our assumption, perceptual actions not only reflect the current situation, but to a certain extent anticipate those of its transformations that can occur as a result of practical actions. Thanks to such sensory anticipation (which, of course, differs significantly from intellectual anticipation), perceptual actions are able to determine the immediate prospects of behavior and regulate it in accordance with the conditions and tasks facing the subject.

Although we studied mainly the processes of vision and touch in a child, the established

the patterns appear to be more general meaning and are manifested in a unique way, as research by our employees shows, in other sensory modalities (in the field of hearing, kinesthetic perceptions, etc.). We studied the dependence of perception on the nature of activity. a) in terms of the ontogenetic development of the child and b) in the course of functional development (in the process of forming certain perceptual actions under the influence of sensory learning). Studies of the ontogeny of perception conducted by us, as well as by other authors, indicate that there are complex relationships between perception and action that change during the development of the child.

In the first months of a child’s life, according to N.M. Shchelovanova, the development of sensory functions (in particular, the functions of distant receptors) is ahead of the ontogenesis of somatic movements and has a significant impact on the formation of the latter. M.I. Lisina discovered that the infant’s orienting reactions to new stimuli very early reach great complexity and are carried out by a whole complex of different analyzers. Despite the fact that at this stage, orienting movements (for example, orienting movements of the eye) reach a relatively high level, according to our data, they perform only an orienting-setting function (they set the receptor to perceive a certain kind of signals), but not an orienting-exploratory function (they do not produce examination of an object and do not model its properties).

As studies by L.A. Wenger, R. Fantz and others have shown, with the help of this kind of reactions already in

In the first months of life, a fairly subtle “approximate” distinction between old and new objects (differing from each other in size, color, shape, etc.) is achieved, but the formation of constant, objective perceptual images, which are necessary for controlling complex changeable forms of behavior, has not yet occurred. .

Later, starting from 3-4 months of life, the child develops the simplest practical actions associated with grasping and manipulating objects, moving in space, etc. The peculiarity of these actions is that they are directly carried out by the organs of his own body (mouth, hands , feet) without the help of any tools.

Sensory functions are included in the maintenance of these practical actions and are rebuilt

on their basis, they themselves gradually acquire the character of peculiar indicative-exploratory, perceptual actions.

Thus, studies by G.L. Vygotskaya, H.M. Haleverson and others reveal that the formation of grasping movements, starting approximately from the third month of life, has a significant impact on the development of perception of the shape and size of an object. Similarly, the progress in depth perception discovered by R. Walk and E. Gibson in children 6-18 months. is associated, according to our observations, with the child’s practice of moving in space.

The unique, direct nature of the infant’s practical actions determines the characteristics of his orienting, perceptual actions. According to L.A. Wenger, the latter anticipate mainly the dynamic relationship between the child’s own body and the object

situation. This occurs, for example, when the infant visually anticipates the route of his movement in given conditions, the prospects of grasping a visible object with his hand.

At this stage of development, the child identifies, first of all, those properties of the object that are directly addressed to him and which his actions directly impinge on, while

time, as a collection of others that are not directly related to it, is perceived globally, indivisibly.

Later, starting from the second year of life, the child, under the influence of adults, begins to master the simplest tools and influences one object on another. As a result, his perception changes.

At this genetic stage, it becomes possible to perceptually anticipate not only the dynamic relationships between one’s own body and the objective situation, but also known

transformations of intersubject relations (for example, anticipating the possibility of dragging a given object through a certain hole, moving one object with the help of another, etc.). Images of perception lose the globality and fragmentation that were characteristic at the previous stage, and at the same time acquire a clearer and more adequate structural structure to the perceived object.

organization. So, for example, in the area of perception of form, the general configuration of the contour gradually begins to emerge, which, firstly, limits one object from another, and secondly, determines some possibilities of their spatial interaction (approximation, overlapping, capturing one object by another, etc.). d.).

Moving from early to preschool age C—7 years), children, with appropriate training, begin to master certain types of specifically human productive activities, aimed not only at using existing ones, but also at creating new objects (the simplest types of manual labor, designing, drawing, modeling, etc.) . Productive activity poses new perceptual tasks for the child.

Research on the role of constructive activity (A.R. Luria, N.N. Poddyakov, V.P. Sokhina, etc.), as well as drawing (Z.M. Boguslavskaya, N.P. Sakulina, etc.) in the development of visual perception show that under the influence of these activities children develop complex species visual analysis and synthesis, the ability to dismember a visible object into parts and then combine them into a single

whole, before this kind of operation is performed in in practical terms. Accordingly, perceptual images of form acquire new content. In addition to further clarifying the outline of the object, its structure, spatial features and relationships begin to stand out

its constituent parts, to which the child had previously paid almost no attention.

These are some experimental data indicating the dependence of the ontogenesis of perception on the nature of the practical activities of children of different ages.

As we have already indicated, the development of a child does not occur spontaneously, but under the influence of learning.

Ontogenetic and functional development continuously interact with each other. In this regard, we can consider the problem of “perception and action” in one more aspect, in the aspect

formation of perceptual actions during sensory learning. Although this process becomes very

various specific features depending on the child’s previous experience and age, however, at all stages of ontogenesis he obeys certain general laws and goes through certain stages, reminiscent in some respects of those established by P.Ya. Galperin and

others when studying the formation of mental actions and concepts.

At the first stage of the formation of new perceptual actions (i.e. in cases where the child is faced with a completely new, previously unknown class of perceptual tasks), the process begins with the fact that the problem is solved in practical terms, with the help of external, material actions with objects . This, of course, does not mean that such actions are performed “blindly”, without any prior orientation in the task. But since the latter is based on past experience, and new tasks are set, this orientation turns out to be insufficient at first, and the necessary corrections are made directly in the process of colliding with material reality, in the course of performing practical actions.

Thus, the above experimental data indicate that children of different ages, faced with new tasks, such as, for example, the task of pushing an object through a certain hole (L.A. Wenger’s experiments) or constructing a complex whole from existing elements (A. R. Luria), initially achieve the required result with the help of practical tests, and only then they develop the corresponding indicative perceptual actions, which at first also have an outwardly expressed, developed character.

Research conducted by us together with the laboratory of experimental didactics of the Institute of Preschool Education (A.P. Usova, N.P. Sakulina, N.N. Poddyakov, etc.) showed that when

In a rational setting of sensory learning, it is necessary, first of all, to correctly organize these

external indicative actions aimed at examining certain properties

perceived object.

Thus, in the experiments of Z.M. Boguslavskaya, L.A. Venger, T.V. Eidovitskaya, Ya.Z. Neverovich, T.A. Repina, A.G. Ruzskaya and others, it was found that the highest results are achieved in the case when, at the initial stages of sensory learning, the very actions that need to be performed, offered to the child

sensory standards, as well as the models of the perceived object created by it, appear in their external material form. This kind of optimal situation for sensory learning arises, for example, in the case when the sensory standards offered to the child are given to him in the form of object samples (in the form of a strip of colored paper, sets of planar figures of various shapes, etc.), which he can compare with perceived object in the process of external actions (bringing them closer to each other, superimposing one on top of the other, etc.). In this way, at this genetic stage, a kind of external, material prototype of the future ideal, perceptual action begins to take shape.

At the second stage, sensory processes, having been restructured under the influence of practical activity, themselves turn into unique perceptual actions, which are carried out with the help of movements of the receptor apparatus and anticipate subsequent practical actions.<...>

We will dwell only on some of the features of these actions and their genetic connections with practical actions.

Research by Z.M. Boguslavskaya, A.G. Ruzskaya and others show, for example, that on at this stage children become familiar with the spatial properties of objects with the help of extensive orienting and exploratory movements (hands and eyes).

Similar phenomena are observed during the formation of acoustic perceptual actions (T.V. Endovitskaya, L.E. Zhurova, T.K. Mikhina, T.A. Repina), as well as during the formation in children of kinesthetic perception of their own postures and movements (I Z.Neverovich). At this stage, examination of the situation with the help of external movements of the gaze, palpating hand, etc. precedes practical actions, determining their direction and nature. Thus, a child who has known experience in passing a labyrinth (experiments of O.V. Ovchinnikova, A.G. Polyakova) can trace in advance the proper path with his eye or palpating hand, avoiding dead ends and not crossing the partitions in the labyrinth.

Similarly, children who have learned in the experiments of L.A. Wenger to drag various objects through holes of different shapes and sizes, begin to correlate them, moving only their gaze from the object to the hole, and after such preliminary orientation, they give an error-free solution to a practical problem.

Thus, at this stage, external indicative and research actions anticipate the paths and results of practical actions, in accordance with the rules and restrictions to which the latter are subject.

At the third stage, perceptual actions are curtailed, their duration is reduced, their effector links are inhibited, and perception begins to give the impression of a passive, inactive process.

Our studies of the formation of visual, tactile and auditory perceptual actions show that at the later stages of sensory learning, children acquire the ability to quickly, without any external orienting and exploratory movements, recognize certain properties of an object, distinguish them from each other, discover connections and relationships between them etc.

Available experimental data suggest that at this stage the external orienting-exploratory action turns into an ideal action, into the movement of attention across the field of perception.<...>

Human Resources for Managers: tutorial Spivak Vladimir Alexandrovich

Labor enrichment

Labor enrichment

There are two known theories related to the content of labor and the functions performed. These theories define a number of general characteristics of work that contribute to increased interest in it, stimulation by the work itself, its content. We are talking about the theory of labor enrichment and the theory of job characteristics (as they are called in the work of D. S. Sink).

Employee responsibility for productivity;

Awareness of the importance and necessity of the work he performs;

Ability to control and independently distribute resources during work;

Feedback, obtaining information about the results of work;

Prospects for professional growth, acquiring new experience, advanced training (the work should not be routine);

The ability to influence working conditions.

Let's go back to job characteristics theory R. Hackman and G. Oldham, which states: the likelihood of a positive psychological state in an individual increases in the presence of five essential aspects of work: variety, completeness, significance, independence, feedback.

In the USA, methods have been developed to identify an employee’s reaction to various components of work using self-report methods and analysis of work attitudes. Based on the assessment of job characteristics by the employee and experts, an indicator of motivational potential is calculated, the value of which is higher, the more attractive the job, the more satisfaction it brings to the employee. Low values of this indicator indicate the need for its redesign.

These factors are essentially within the competence of each manager; they are associated with a competent, humanistic, individualized organization of work. If it is necessary to perform routine work that does not contain all the necessary attractiveness factors, or work that does not correspond to the professionalism, inclinations, and inclinations of the employee, the first priority comes to the requirement to apply the theories of motivation discussed in Chapter. 2.

Based on the proven fact that satisfaction with the content of work increases productivity and results, modern American scientists study work attitudes (attitudes towards work) using the following methods:

Determination of the descriptive index of work;

Determination of the index of organizational decisions;

Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire;

Job satisfaction scale;

Method of subjective analysis of works and others 6.

For example, employees' self-reports, presented in the form of a “Diagnostic Job Assessment” and a “List of Job Aspects,” are examined as a manifestation of a reaction to job characteristics (according to the theory of job characteristics). Special research methods make it possible to obtain a quantitative expression of work parameters, such as the required variety of skills, completeness and significance of the work, independence and responsibility combined with a certain freedom in choosing methods for its implementation, and the presence of feedback to evaluate the results of efforts. The obtained data are used to calculate the indicator of motivational potential of work (PMP) according to the following formula:

A low level of PMP indicates the need to redesign the work.

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology has carried out a fairly extensive research project related to career planning. This work was initiated in response to the observation that some engineers had lost interest in technology and were instead becoming interested in problems of human behavior. The second group of engineers completely lost motivation for work and turned their activity to family and hobbies. Thus, the number of engineers interested in technology was constantly decreasing.

The study covered 3 thousand people working at different levels and in various positions. Based on the study, five most important factors influencing job satisfaction and motivation were identified.

1. The variety of work requirements for skill (self-expression). In practice, it is about the extent to which people can use their strengths at work, and the match between the demands of the job and their skill level. In other words, the work should be varied, developing and challenging.

2. Clarity of task content, causing a feeling of identification with the work (the work as it is). If the first can be considered a structural moment, then identification seems to be an activating factor. In other words, the task should be specific, the result of its implementation measurable, and the content of the work should make it possible to say: “This is the work for me, only I can do it, in it I will express myself.”

3. An idea of the significance of the task for the organization (value, status). Feeling the importance of work and assumption

How others perceive your work combine to form a central factor of motivation. Work should be meaningful, not for show or for the basket.

4. Feedback. Positive or negative reinforcement received from a boss, colleagues or subordinates and associated with job success increases job satisfaction. Opining others' performance in itself increases motivation, while saying nothing reduces feelings of satisfaction. Feedback should be prompt and effective, its purpose is to reinforce correct behavior or stop incorrect behavior.

5. Self-activity. The ability to work independently and the balance of power and responsibility is the fifth factor influencing job satisfaction. The same thing can be expressed in other words: self-discipline is the price of freedom. Usually people are willing to pay this price. This reasoning corresponds to the model Y labor behavior according to McGregor. We are talking about independence in planning and organizing one’s own work and managing resources, which presupposes organization and responsibility of the employee.

There are no money or other material rewards among the factors influencing job satisfaction. According to data for 1993, annual income engineer in the USA was $55.8 thousand per year, which, apparently, is perceived by engineers as a completely sufficient level to ensure a decent living. In general, material factors act as short-term incentives; a person quickly adapts to new possibilities of existence. A decent salary, according to F. Herzberg, increases job satisfaction, but does not contribute to an increase in the employee’s output or growth in his labor productivity.

There is probably nothing radically new in the very set of factors influencing job satisfaction. As a refreshing observation, they motivate differently at different stages of tenure. The decisive point is the duration of a person’s performance of the same work, which does not change in content.

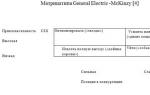

In Fig. Figure 3.1 shows the influence of these five factors on job satisfaction at different stages of tenure in one position. A significant impact on job satisfaction is reflected only by those parts of the curved lines that are located above the dotted line.

Rice. 3.1. The weight of job satisfaction factors at different stages of tenure

In the first year of work (whether it is the first or the sixth job), the motivators are the idea of the meaning of the task and feedback. Independence is of interest between the second and fifth years - at this time it is the most important factor of motivation. The presence of feedback is of interest during the first three years. After two or three years of working in one place, a person is “in the prime of his life.”

The main thing is what is shown in Fig. 3.1, – after five years of work in the same place, not a single factor ensures job satisfaction and, as a result, achievements in work are significantly reduced. Instead of factors related to work, motivation is born from selfish motives, such as travel, entertainment, hobbies work time, anticipation of pension, benefits for staff. What can an enterprise do to reverse such an unfavorable situation? The most important activities to maintain motivation are the following.

1. Systematic review of the tenure of personnel in one position and controlled horizontal movement at intervals of approximately five years. Horizontal movements must be made prestigious. It is also necessary to approve and make it prestigious to move down in the service hierarchy at some stages of the career.

2. Enrichment of the content of the work and expansion of its scope (have an impact up to 5 years).

3. Active structural planning of the organization and the use of flexible organizational forms(project, matrix organization).

4. Systematic development organizational activities, learning and creativity.

5. Implementation of new forms of interaction, for example, conversations between a boss and a subordinate as an integral part effective management, industrial democracy 7 .

Practical implementation theories related to the content and conditions of work takes the following forms 8:

change of workplace (rotation)– systematic rotation allows you to avoid one-sided loads, monotony, ensure diversified qualifications and wider use of personnel;

expansion of the field of activity– combining several homogeneous work steps or production tasks into one larger production task, that is, horizontal expansion of the field of activity;

enrichment of work content– vertical expansion of the field of activity by including tasks of preparation, planning, control, etc., that is, an increase in the intellectual component of activity;