Medium bomber Douglas DV-7A (A-20A). The American plane was regarded by us as a short-range bomber, and not as an attack aircraft. What was considered a medium bomber in the USA, by our standards, was already closer to our long-range bombers, and in terms of weight, crew composition and defensive weapons, it was out of this category.

"Bostons" have earned an excellent reputation among our pilots. These machines had good flight qualities for that time. They could compete with German technology in speed and maneuverability." When B-3s appeared on the Soviet-German front, they overtook our new Pe-2s. The American bomber was distinguished by good maneuverability and a large service ceiling. Deep turns were easy for him, he flew freely on one engine. Considering the poor training of pilots who were quickly graduated from schools during the war, the aerobatic qualities of the aircraft became very important. Here the Boston was excellent - simple and easy to control, obedient and stable on turns. Takeoff and landing on it were much easier than on the domestic Pe-2.

The motors worked reliably, started well, but with very intensive use they did not reach the prescribed service life. It was necessary to break the seals supplied by the Americans and change the pistons, cylinders, piston rings and bearings. But it should be taken into account that the nominal life of the “rights” exceeded the life of all domestic aircraft engines twice, or even three times.

The A-20 cockpits were spacious, and both the pilot and navigator had good review, they were located in comfortable armchairs with armor protection. The cabin was heated, which after our frozen SB and Pe-2 seemed an unthinkable luxury.

But the first combat experience showed weak points American aircraft, primarily defensive weapons. The Bostons had been vulnerable to attacks from behind even earlier, suffering heavy losses from German fighters. We quickly realized that Boston's firepower was insufficient and decided to take measures to increase it. Urgent development of Boston re-equipment projects began. The first such alterations were carried out directly, at the front. Instead of Brownings, they installed domestic UB heavy machine guns. The upper installation with coaxial machine guns, which had an insufficient field of fire, was replaced with an MV-3 turret with a ShKAS machine gun or with a UTK-1 with an UBT. The GKO decree of September 24 approved the rearmament scheme proposed by the Design Bureau of Plant No. 43: two fixed UBCs on the sides of the navigation cabin, on top of a UTK-1 with a UBT and another UBT in the hatch on the installation from the Pe-2. All B-3s (i.e. DB-7B, DB-7C and A-20C) were subject to conversion. The first 30 aircraft needed to be re-equipped already in September 1942. And indeed, in September, Bostons with Soviet machine guns already began operating at the front. At the same time, the aircraft’s armor protection was strengthened and modifications were made for winter operation.

On the A-20B there was a large-caliber machine gun on top, but in the same pivot mounting. Not much has changed in better side and bomb weapons. It was considered that this option was also not satisfactory and they also began to redo it. In December 1942, the simplest modification of this modification was submitted for testing - standard American bomb racks (the A-20B had six of them inside and four outside) were simply modified to fit our bombs. And in June 1943, NIPAV tried a more advanced processing: our Der-21 cluster bomb racks, designed for a total of 16 FAB-100 bombs, were installed in the internal bomb bays, and Der-19P was installed outside for bombs with a caliber of up to 250 kg. Der-21 made it possible to insert cassettes of small KMB - Pe-2 bombs into bomb bays under AO-2.5, AO-10, AO-25, ZAB-2.5 bombs and AZh-2 ampoules (usually filled with self-igniting liquid). On the outside, we provided for the suspension of chemical pouring devices VAP-250. We installed the ESBR-6 bomb release device, OPB-1R and NKPB-7 sights. As a result, the maximum bomb load (when taking off from concrete) increased to 2000 kg. A total of more than 600 aircraft, including several hundred A-20Bs, underwent replacement bomb armament. Changes in the defensive armament of vehicles of this type were mainly limited to the installation of the UTK-1 upper turret. But it was not the Soviet UBT machine gun that was mounted in the turret, but the American Colt-Browning, removed from the standard pivot mount. On October 31, 1942, Deputy Air Force Commander Vorozheikin addressed the NKAP with a request to urgently modify 54 A-20Bs according to this scheme.

In 1943, it began to arrive through Alaska and Iran. new modification- A-20G (we usually designated A-20Zh, hence one of its nicknames - “Bug”). This was the next mass production version of the Boston. Before it, American designers created several modifications that were not put into mass production. The A-20D remained an unrealized project for a lightweight version of the A-20B with R-2600-7 turbocharged engines. Seventeen A-20Es were conversions of the A-20A with unprotected gas tanks for training purposes. The experimental XA-20F was further development XA-20V and had a 37-mm cannon in the nose. The next widespread (and ultimately the most widespread - 2850 copies) modification of the Havok was the A-20S. This was a purely assault version. The bow section was now occupied by a whole battery of cannons and machine guns. The first series, the A-20G-1, had four 20mm M2 cannons with 60 rounds of ammunition each and two 12.7mm machine guns in the nose. At the same time, the armor shield was strengthened, the aircraft's equipment was improved and the bomb load was sharply increased (with an overload of up to 1800 kg), while lengthening the rear bomb bay. The vehicle became heavier (the empty weight of the aircraft increased by more than a ton), losing somewhat in speed and maneuverability and considerably in the ceiling, but its combat effectiveness increased. Almost all G-1 type aircraft were sent to the USSR. Nose guns were soon abandoned.

Starting with the G-5 series, six heavy machine guns began to be installed. On the G-20, the rear part of the fuselage was expanded and an electrified Martin 250GE turret with two 12.7 mm machine guns was mounted there (this turret was first tested on one of the production A-20Cs). At the lowest point there was now the same machine gun. The A-20G aircraft were also externally distinguished by individual exhaust pipes on the engines instead of a common manifold, and by the ring antenna of the MN-26Y radio half-compass on top. The A-20G-20 was tested at the Air Force Research Institute in October 1943. From series to series, the Boston was equipped with more and more effective weapons, the bomb load was increased, and armor protection was improved, but the aircraft became increasingly heavier, losing in flight performance. It was already inferior in speed to the latest series of Pe-2, but still remained a formidable front-line bomber.

The first A-20G appeared on the Soviet-German front in the summer of 1943. The A-20G became a truly multi-purpose aircraft in our aviation, performing a variety of functions - day and night bomber, reconnaissance aircraft, torpedo bomber and minelayer, heavy fighter and even transport aircraft. It was rarely used only as an attack aircraft - for its main purpose! As already mentioned, the A-20G was very vulnerable to anti-aircraft gunners at low altitudes due to its considerable size and weak armor cover. Only when surprise was achieved could one count on the comparative safety of the Boston during an attack in the conditions of well-functioning German air defense. Nevertheless, our pilots carried out assault strikes on convoys, trains, and ships. The crews of the 449th Regiment in such a situation usually attacked from a height of 300-700 m, diving at an angle of 20-25 degrees. After a burst of 20-30 shells, a quick departure at low level followed. The place of the attack aircraft in our aviation was firmly occupied by the Il-2, and the A-20G was forced out into other areas of application. To perform functions not provided by the designers (or provided insufficiently), the machine had to be modified in one way or another. For example, the A-20G was inconvenient for use as a bomber due to the lack of a navigator's seat.

If in 1943 in Soviet Union 1,360 A-20 aircraft of various modifications were received, in 1944 - 743, in 1945 only one Boston passed through Soviet military acceptance. Together with the A-20G and A-20J, their “younger brothers” - the A-20N and A-20K - took part in the final phase of the war, indistinguishable from them in appearance, but equipped with more powerful R-2600-29 engines, boosted to 1850 hp, which slightly increased the speed. Compared to the A-20G, all other modifications were built in small numbers: A-20J - 450 copies, A-20N - 412, A-20K - 413. A-20N and A-20K became the last representatives of this family. In 1944, on the assembly lines of the Douglas company, they were replaced by new machines of the same purpose - the A-26. The lion's share of aircraft of modifications N and K went to the Soviet Union. One of the A-20K-11s was tested at the Air Force Research Institute in October 1944. However, by the time the war with Germany ended, only about a dozen of these bombers reached the front. The rest arrived later, in preparation for the campaign against Japan. And in 1945, the re-equipment of new regiments with Bostons continued.

On May 1, 1945, the Soviet Air Force had 935 Bostons. More than two-thirds of them were modification G machines. There were only 65 new A-20J and A-20K. But it should be noted that a significant part of the Bostons went into naval aviation, which will be discussed below.

It is interesting to compare the evolution of the Boston with similar multi-purpose vehicles that were in service with our allies and enemies during the war. The same age as the A-20, the English Blenheim, was much lighter, carried a smaller bomb load and was significantly inferior to it in speed. Two American light bombers exported to England, the Maryland (Martin 167) and the Baltimore (Martin 187), were not much superior to the Blenheim in their flight performance, losing to the Boston in a maximum speed of 50-100 km/h. Only Mosquito, created much later, had a significant advantage in almost all respects. The German medium bombers Juncker Ju 88A and Do 217E were significantly heavier (including due to a significantly larger bomb load and range) and, naturally, were inferior in speed and ceiling. Aircraft of the same purpose, which were in service in Italy and Japan, could in no way be compared with the Boston.

Our main front-line bomber was the Pe-2 for almost the entire war. The evolution of the Pe-2 and A-20 has a number of similarities, but also has significant differences. When they first met on the Soviet-German front in the spring of 1942, their flight qualities were approximately equivalent: the Boston, although heavier, won in speed of 10-15 km/h, but was slightly behind the Pe-2 in practical ceiling. Subsequently, both vehicles were improved, the power of the engines grew, the armament became stronger and the equipment became more complex. This is where the approach of Soviet and American designers turned out to be completely different. Although both of them focused on improving performance primarily for low and medium altitudes, for the Americans, the entire increase in thrust went to partially compensate for the sharply increased bomb load and more powerful (and heavy) weapons, while the flight performance of the vehicle fell by Pe -2, the weight of the bombs remained unchanged, and after 1943, both speed and ceiling began to increase. In general, in terms of its size and weight characteristics, the A-20 was closer not to the Pe-2, but to the Tu-2 that appeared later, which had engines of approximately the same power. During the war, the Boston became a multi-purpose vehicle, demonstrating significantly greater capabilities than the Pe-2.

In total, 3,125 A-20 Havoc aircraft were delivered to us under Lend-Lease.

: 09.08.2016 20:49

I quote Mushroom yes yes yes - I wrote from memory so I was mistaken - one B 17 was used for its intended purpose in 1945, a total of 23 aircraft from among those that crashed on the territory of the USSR were restored, but that’s not the point - the idea is clear - in 1943 they weren’t even close

: 09.08.2016 20:18

I quote Major about 43, I meant that several cars ended up in the USSR after being interned in the Far East in 44, but not in 43 Are these the ones who used USSR airfields under an agreement in the western USSR? Are you confusing it with the B-29s that grounded in the east due to problems?

: 09.08.2016 17:29

: 09.08.2016 09:33

I quote Major Oh, and you fill it up... B 17 is a torpedo bomber)), then Po 2 is a high-altitude interceptor, and with 43m it got too excited... The memoirs described how Gromov’s delegation to the United States had already received consent to supply B-17s, but this matter was immediately killed by the American Minister of Defense. And they installed B-25s instead of the 17th. So there were no “Flying Fortresses” in the USSR at all. Alexey confused |

In 1943, composer Jimmy McHugh wrote a song to the words of Harold Adamson, which quickly became the leader of the charts and, unprecedentedly, was relatively close to the text and translated into Russian. Performed by Leonid and Edith Utesov, it was heard in the Soviet Union, it was sung in the streets, and it was heard in Soviet films. The last (in time) of the films in which this song is heard, if I’m not mistaken, is “In the Special Attention Zone.”

Here are the original lyrics of the song:

Two hours overdue

One of our planes was missing

With all it's gallant crew,

The radio sets were humming,

They waited for a word,

Then a voice broke through the humming

And this is what they heard:

"Comin" in on a wing and a prayer,

Comin" in on a wing and a prayer,

Though there's one motor gone

We can still carry on,

Comin" in on a wing and a prayer.

What a show! What a fight!

Yes, we really hit our target for tonight!

How we sing as we limp through the air,

Look below, there"s our field over there,

With our full crew aboard

And our trust in the Lord

We"re comin" in on a wing and a prayer"

And here is its Russian version:

Our very airy people were concerned -

The plane did not return to us from the bombing at night.

The radio operators scraped the air, barely catching the wave,

And then at five minutes to four they heard the words:

“We fly, hobbling in the darkness,

We are crawling on the last wing,

The tank is broken, the tail is on fire, but the car flies

On my word of honor and on one wing.

Well, there you go! It was night!

We bombed their facilities to the ground!

We left, hobbling in the darkness,

We are approaching our native land.

The whole team is safe, and the car has arrived -

On my word of honor and on the same wing.”

It is unlikely that the Averykans had in mind the North American (the same company that produced the P-51 Mustang) B-25 Mitchell; rather, they wrote about the B-17 Flying Fortress, but did not receive Fortresses in the USSR. But they received twin-engine bombers B-25 and A-20, and through the censorship it was possible to push this song of bomber pilots under these legendary machines, which were distinguished by absolutely incredible survivability, actually arriving from missions on one engine, broken, crumpled, shot through, but alive and with a live crew.

The B-25 became legendary after the raid on Tokyo, a gift for Emperor Hirohito’s birthday. The same raid by Colonel Doolittle, when 16 Mitells took off from the deck of the aircraft carrier Hornet and bombed Japan.

It must be said that the Americans supplied only 862 vehicles under the Lend-Lease program. Either the Soviet representatives no longer ordered them, or the Americans huddled - they themselves needed them in all theaters of military operations. The American Air Force used the B-25 both as a medium bomber and as an attack aircraft (they placed as many as 8 12.7 mm machine guns on the nose and sides of the fuselage). Despite the low speed and altitude, the Americans could afford to use Mitchells in this way, since they always provided them with powerful fighter protection.

The first combat military unit of the Soviet Air Force to begin mastering the B-25 bomber in the summer of 1942 was the 37th BAP, which arrived from the Far East at the Kratovo airfield in the Moscow region. Soon it was joined by two more bomber regiments: the 16th and 125th, which until that time had fought on the Leningrad Front on Pe-2 aircraft. From these regiments, in July 1942, the 222nd BAA was formed, which from August 8 took part in hostilities as part of the 1st BAC. For daytime work on the Soviet fronts, the B-25s turned out to be of little use and suffered heavy losses.

The Mitchells were soon transferred to long-range bomber aircraft, which flew at night. In 42-43, the basis of ADD (long-range aviation) was the Ilyushin TB-7, DB-3 (IL-4) and... Li-2. For 1936, when the DB-3 was created, this car was relatively good. But her piloting was simply inhuman. The plane did not have an autopilot, it constantly yawed, lost its course, and the pilot had to “turn the wheel” all the time, exerting quite a lot of physical effort. The further, the more duralumin structures were replaced by wooden ones, which is why, of course, the aircraft did not win at all in terms of any characteristics. The engines were capricious, there was practically no instrumentation, radio communications were poor, but a lot of them were built and they were used very actively, despite catastrophic losses. In August 1941, they took part in raids on Königsberg, Stettin and Berlin. They say that once American pilots begged to take them for a ride in an Il-4. After the flight they came out staggering. Having caught their breath a little, they said that Russian guys are real heroes if they fly on this...

The performance characteristics of Mitchell and IL-4 were approximately the same. Approximately the same maximum speed (442 for the B-25 versus 430 for the Il-4), the altitude of the Il was 1.3 km higher (7600 versus 8900 m), the combat radius was about 1000 km, the bomb load was approximately the same, only defensive weapons the B-25 was more serious. But Ilya “withstood the blow” extremely poorly. Even a hole in the wing threatened the inevitable death of the vehicle, and the Mitchells were exceptionally tenacious.

Soviet pilots noted the amenities for the crew, the presence of 2 pilots, the heating of the cabin, the presence of such little things as an anti-icing device for the cabin glazing (on the Il-4 the pilot was instructed to open the windows and wipe the glass from the outside with a cloth... in flight!). American designers, like no other, understood that 75% of the effectiveness of military equipment depends on the training and condition of the crews. Therefore, it is interesting to read what Soviet pilots who flew the B-25 wrote:

The pilots' first impression of the car was unimportant. They immediately nicknamed her “cuttlefish.” The tail-keel with the pipe up and the three-wheeled landing gear seemed very clumsy. But after flying it, we changed our attitude. The plane was very easy to taxi with excellent forward visibility. Piloting both on takeoff and in the air and on landing was so simple that it made it possible to quickly introduce young pilots into combat formation. Of all the types of aircraft I have flown, the B-25 is the most accessible in terms of flying technique. Two keels with rudders in the sphere of action of the jet from the propellers and a three-wheeled landing gear made it possible to take off and land in any crosswind. It is no coincidence that subsequently all aviation switched to a three-wheeled landing gear.

The B-25 was equipped with flight and navigation instruments that were remarkable for those times. It had two attitude indicators - for the left and right pilots, a good autopilot, which provided great assistance to pilots during long and “blind” flights, and most importantly, a radio compass, which was indispensable in night flights. Of particular note is the aircraft's anti-icing system, which allowed it to fly in any weather. On the attack ribs of both planes there was a mechanical de-icer from Goodrich. Rubber “bags” were periodically inflated, chipping off the ice, and the screws were washed with alcohol.

It is necessary to say about the reliable operation of the motors, which had a total service life of 500 hours. And the Wright-Cyclone engines produced it. Of course, there were refusals - aviation is not without it. My pilot, senior lieutenant Nikolay Sidun, had one of his engines disabled by a direct hit from an MZA shell in the sky over Budapest. He managed to “pull” over the Carpathians on the second, arrive at his Uman airfield and land safely. The flight on one engine lasted for 3 hours....My crew had to fly a lot to drop reconnaissance aircraft over the entire territory of Europe, including the Berlin area. In this case, a tank with a capacity of 518 gallons was suspended in the bomb hatch, and then it was possible to remain in the air for 15 hours without landing. The scouts jumped out at an altitude of 300-400 m through a hatch in the navigator's cabin. In just the years of the Great Patriotic War I completed 220 combat missions...

...Due to successful military operations, our regiment of the 125th BAP ADD was transformed into the 15th Guards BAP ADD, which received the name "Sevastopol".

The American B-25 aircraft was widely used by our aviation due to another important advantage. There were two pilots on it, and we trained only the pilots who sat in the right seat on this machine to become the crew commander, because they acquired good combat experience and were excellent at instrument piloting.

I confess: throughout my entire flying career I have had two favorite aircraft - the B-25 and Tu-16. But "Mitchell" is something closer to the heart. Apparently because he once saved my life during the war.

Well, and finally, as usual, 2 films.

The second aircraft mentioned in the first film is the Douglas A-20 Havoc, which received the name Boston in the USSR.

Under the Lend-Lease program, significantly more of these aircraft were delivered to the USSR than Mitchells - 3,414 aircraft.

The A-20 was a fairly nimble light front-line bomber with maximum speed 560 km/h, combat radius 600 km, service ceiling 8650 m and with a bomb load of 900 kg.

These aircraft were successfully used by Soviet pilots as bombers, reconnaissance aircraft and heavy fighters. The role was especially great in naval aviation, primarily in mine and torpedo regiments. The A-20 became the best Soviet top-mast aircraft. Top-mast bombing is the dropping of bombs at high speed and from a low altitude, so that the bombs, bouncing off the surface of the widow, jump off the board enemy ship and exploded upon impact with its side or superstructure.

Soviet pilots unanimously recognized that the Boston fully meets the requirements of modern warfare. The bomber had a good thrust-to-weight ratio, which ensured high speed, good maneuverability and quite a decent ceiling. It was easy for him to take deep turns with maximum roll; he flew freely on one engine. The Soviet instructions for Boston piloting techniques stated: “Flight... with one running engine is not particularly difficult.” Considering the poor training of pilots who were quickly graduated from schools during the war, the aerobatic qualities of the aircraft were very important. Here the Boston was excellent - simple and easy to control, obedient and stable on turns. In terms of difficulty of piloting, it was rated at the level of our Security Council. Takeoff and landing on an American bomber with a three-wheeled landing gear were much easier than on the domestic Pe-2. Again, ah The Americans, compared to Soviet designers, paid more attention to the comfort of the crew. The A-20's cabin was spacious. Both the pilot and the navigator had a good view; they were located in comfortable armchairs with armor protection. Our pilots were amazed by the abundance of instruments on a relatively small machine, including gyroscopic ones. The aircraft had a full set of modern navigation and radio equipment. A sharp expansion in the use of Bostons at sea occurred after the arrival of the A-20G modification to the USSR. It was a purely assault variant without a navigator's seat in the nose, replaced by a battery of four 20 mm cannons (on the 0-1) or six 12.7 mm machine guns (on all subsequent G and H). The lion's share of aircraft of modifications G, H went to the Soviet Union, starting with almost all A-20G-1. These vehicles were transported both through Alaska and Iran. For example, the 1st Guards Mine and Torpedo Regiment received the A-20G-1. The Boston occupied a special place in the role of a torpedo bomber, minelayer and top-mast carrier. During the war years, it became, perhaps, the main aircraft of our mine-torpedo aircraft, seriously displacing the Il-4.

In the USSR, Bostons remained in service longer than in the USA and Great Britain. Total for 1942 - 1945 Navy aviation received 656 foreign torpedo bombers, which by the end of the war made up 68 percent of mine-torpedo aircraft. If we discard the 19 English Hampdens, then everything else is Bostons of various modifications. A-20Gs were seen in the Baltic back in the 1950s. The 9th Guards Regiment in the North, already flying Tu-14 jets, retained a mothballed set of Bostons until 1954.

Boston A-20

The American bomber Douglas A-20 (aka Boston, Havoc) is one of the most famous aircraft supplied under Lend-Lease during the Great Patriotic War. These aircraft were successfully used by Soviet pilots as bombers, reconnaissance aircraft and heavy fighters. The role was especially great in naval aviation, primarily in mine and torpedo regiments.

It is interesting that the future Boston began to be designed in 1936 as a purely land attack bomber (“model 7A”). Its creator, J. Northrop, never imagined that this machine would ever be used against ships. Since 1939, the aircraft went into mass production under the DB-7 brand. various options for the US Army Air Forces (like the A-20), British and French military aviation. But all these options were also purely land.

Dutch specialists were the first to draw attention to the potential capabilities of the DB-7 in the field of combat operations at sea. In October 1941, after the Germans had captured the Netherlands itself, the government of the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) ordered a batch of DB-7C aircraft from the United States. According to the order issued by the customer, this version was supposed to be similar to the DB-7B built for Great Britain, but would be able to carry a torpedo weighing 907 kg. It was located in the lower part of the bomb bay in a recessed position with the hatch doors removed. The DB-7C also had a sea rescue kit with inflatable boat. Aircraft began arriving in the East Indies after the start of hostilities in the Pacific. 20 DB-7C in containers arrived on the island. Java shortly after the Japanese invaded it. Only one aircraft was fully assembled, which took part in the battles for the island, and the rest, intact or damaged, went to the invaders as trophies. It was never possible to test the DB-7C torpedo suspension in real life.

The experience gained on the DB-7C was used on the A-20C modification. This variant, also known as the Boston III, received a torpedo suspension similar to the DB-7C, which later became standard for all modifications.

A-20s were used by American army aviation against warships and especially transport ships (mainly in the Pacific Ocean), but they operated only with machine gun fire, bombs and rockets. The US Navy used a limited number of A-20s only for auxiliary purposes - as target tugs. The coastal command of the British Air Force did not have Bostons at all.

A-20Cs made up the bulk of the first batches of bombers transferred by the USSR's allies. Along with them came a number of DB-7B and DB-7C. The Soviet mission began accepting Bostons in Iraq in February 1942. Already at the end of spring these planes appeared at the front. In the fall of the same year, they, along with another modification, the A-20B, went along the route from Alaska to Krasnoyarsk. Soviet naval aviation first tried to operate Bostons in early 1943.

Since January, the 37th Guards Mine and Torpedo Regiment began operating on the Boston III in the Black Sea. He carried out raids on Crimea from Gelendzhik. However, the Boston III, as well as the A-20B, was difficult to use in its original form as a bomber at sea. Two already mentioned circumstances interfered: the relatively short range (the range was 1380 km - less than that of our Pe-2) and the impossibility of hanging large bombs necessary to destroy warships. Therefore, the Bostons were first used in the navy mainly as reconnaissance aircraft. For example, in the Baltic, the 1st Guards Mine and Torpedo Regiment received six A-20Bs in February 1943, tested them... and handed them over to the reconnaissance regiment. On the Black Sea, Bostons were equipped with the 1st squadron of the 30th separate reconnaissance regiment (and since the summer of 1943, the 2nd).

When converting to a reconnaissance aircraft, an additional gas tank was installed in the bomb bay. Photographic equipment (cameras of types AFA-1, AFA-B, NAFA-13 and NAFA-19) was placed in the radio operator’s cabin and partially in the bomb bay.

The first Bostons to enter service with the Navy allowed for a comprehensive assessment of the capabilities of this very promising aircraft. They also carried out major modifications that increased the effectiveness of their combat use.

Our pilots unanimously recognized that the Boston fully meets the requirements of modern warfare. The bomber had a good thrust-to-weight ratio, which ensured high speed, good maneuverability and a fairly decent ceiling. It was easy for him to take deep turns with maximum roll; he flew freely on one engine. The Soviet instructions for Boston piloting techniques stated: “Flight... with one running engine is not particularly difficult.” Considering the poor training of pilots who were quickly graduated from schools during the war, the aerobatic qualities of the aircraft were very important. Here the Boston was excellent - simple and easy to control, obedient and stable on turns. In terms of difficulty of piloting, it was rated at the level of our Security Council. Takeoff and landing on an American bomber with a three-wheeled landing gear were much easier than on the domestic Pe-2.

The operational capabilities of the Boston were also important for the harsh conditions of the Soviet-German front. The Wright engines worked reliably and started well, although in the Arctic they were noticed that they were very sensitive to hypothermia. There, the Bostons were equipped with devices for regulating the blowing of the cylinders - frontal controlled blinds, similar to those mounted on the Il-4. Sometimes the propeller pitch control mechanisms froze, which forced the propeller bushings to be insulated with removable caps. During very intensive use in the USSR, the motors did not reach the prescribed service life between bulkheads. It was necessary to break the seals supplied by the Americans (the company guaranteed 500 hours) and change the piston rings, pistons, cylinders and bearings. Sometimes air got into the Stromberg carburetors due to a leak in the filter connections - this led to the engine stopping in flight.

The Americans, compared to Soviet designers, paid more attention to the comfort of the crew. The A-20's cabin was spacious. Both the pilot and the navigator had a good view; they were located in comfortable armchairs with armor protection. Our pilots were amazed by the abundance of instruments on a relatively small machine, including gyroscopic ones. The aircraft had a full set of modern navigation and radio equipment. Our Boston crew has been increased by adding a separate lower gunner to the radio operator.

In general, "Boston" fully met the requirements of the war on the Soviet-German front. The main disadvantage of this vehicle was its weak defensive weapons.

The second significant drawback was considered to be the small bomb load (for all early modifications 780 - 940 kg), which was limited, however, not so much by the capabilities of the propeller-engine installation, but by the number of bomb racks and the size of the bomb bay. The A-20 was not designed to carry large bombs. This is quite understandable: the “five hundred” did not fit into the concept of an attack aircraft.

The A-20S, just like the Boston III, was first redesigned in military units, and then on a factory scale, strengthening its armament. Instead of a pivot mount with two machine guns of 7.62 or 7.69 mm caliber, domestic turrets were mounted under a large-caliber UBT machine gun, and sometimes even a ShVAK cannon.

This modification increased the aircraft's weight and drag, for which one had to pay with a loss of speed (6 - 10 km/h), as well as a reduction in the normal bomb load to 600 kg. Most often they installed the UTK-1 turret with one UBT and a K-8T sight or a PMP with 200 rounds of ammunition. A Pe-2 hatch installation with an OP-2L sight and a supply of 220 rounds of ammunition was mounted below. This version was produced by the Moscow aircraft plant N 81, which during the war specialized in the repair and modification of foreign aircraft. In total, about 830 bombers were converted in this way (including the A-20C of the early series, which will be discussed later).

Sometimes, in parallel, on vehicles of the Boston III and A-20S types, the bow machine guns were also replaced with Soviet UBKs. The machine guns in the engine nacelles on some aircraft were usually removed. American bomb racks were modified to hang our bombs without adapters, and then Soviet holders Der-19 and KD-2-439 and KBM-Su-2 cassettes were installed, which made it possible to increase the bomb load.

The largest number of proposals for modifications concerned the DB-7C, which, according to all documents, was officially classified as a torpedo bomber. It was the first to introduce external suspension of two torpedoes using so-called torpedo bridges (this work was carried out by the already mentioned plant╧ 81) and additional gas tanks with a capacity of 1036 liters in the bomb bay (they were offered in the Baltic). These two characteristic features then they appeared on all Boston mine-torpedo aircraft.

This, of course, did not exhaust the variety of engineering ingenuity applied in the fleets to the modernization of American bombers. So, in the north, the DB-7C was converted into an attack aircraft, very similar to the “gunship” - a gunboat based on the A-20A, used by the Americans in New Guinea. There were many different training options with dual controls.

A sharp expansion in the use of Bostons at sea occurred after the arrival of the A-20G modification to the USSR. It was a purely assault variant without a navigator's seat in the nose, replaced by a battery of four 20 mm cannons (on the 0-1) or six 12.7 mm machine guns (on all subsequent G and H). The lion's share of aircraft of modifications G, H went to the Soviet Union, starting with almost all A-20G-1. These vehicles were transported both through Alaska and Iran. For example, the 1st Guards Mine and Torpedo Regiment received the A-20G-1.

The place of the attack aircraft in our aviation was firmly occupied by the Il-2, and the A-20G was forced out into other areas of application. To perform functions not provided for by the designers, the machine had to be modified in one way or another.

The Boston occupied a special place in the role of a torpedo bomber, minelayer and top-mast carrier. During the war years, it became, perhaps, the main aircraft of our mine-torpedo aircraft, seriously displacing the Il-4.

"Bostons" were in service with mine and torpedo aircraft of all fleets. In the North they were flown by the 9th Guards Mine and Torpedo Regiment, in the Baltic by the 2nd Guards and 51st, and on the Black Sea by the 13th Guards. And the 36th mine and torpedo regiment was first transferred from the Black Sea to the Northern Fleet, and then in August 1945 - to the Air Force of the Pacific Fleet.

When converting the A-20G into a torpedo bomber, as well as into a reconnaissance aircraft, an additional gas tank was installed in the bomb bay, which made it possible to approximately equalize the range of the Boston and the IL-4. Sometimes a navigator's cabin was made in the bow. The second common option was for the navigator to sit behind the rear shooting point. There were side windows for the navigator, and above them there was a small transparent dome. It must be said that this placement of the navigator’s seat was not very convenient due to the severely limited view. However, the standard A-20G nose was retained. In an attack, such vehicles were usually launched first to suppress anti-aircraft fire from ships. Sometimes the navigator was located immediately behind the pilot's cabin in a lying position.

In order for the aircraft to carry torpedoes, so-called torpedo bridges were placed on the sides on the left and right in the lower part of the fuselage under the wing. They were an I-beam (often welded or riveted from two channels) with wooden fairings at the ends, attached to the fuselage by a system of struts. Theoretically, it was possible to take two torpedoes in this way (and they sometimes flew at close distances from hard ground), but usually they hung one on the starboard side.

Torpedo bridges were made both directly in units and in various workshops. In this case, American underwing bomb racks were removed. A trial conversion of the A-20G-1 into a torpedo bomber was carried out in the spring of 1943 in Moscow at the plant╧ 81 on one of the vehicles received by the 1st Guards Mine and Torpedo Regiment (plane of A.V. Presnyakov, later Hero of the Soviet Union).

Soviet naval pilots won many victories with the torpedo-carrying A-20G. "Bostons" usually acted as a so-called "low torpedo bomber" - they dropped torpedoes at a distance of 600 - 800 m from the target from a height of 25 - 30 m - from a strafing flight. The speed of the aircraft was approximately 300 km/h.

This tactic was very effective. For example, at dawn on October 15, 1944, Northern Fleet aviation launched a massive attack on one of the German convoys: 26 ships covered seven enemy fighters. The first to attack were 12 Il-2s, then an hour later another 12 attack aircraft. They were followed by a third wave of 10 A-20Gs accompanied by 15 fighters. Several ships were sunk. The fourth wave completed the matter. Ten A-20Gs were led by the commander of the 9th Guards Regiment, Lieutenant Colonel B.P. Syromyatnikov. His plane was shot down by the Germans, but Syromyatnikov was hit by a transport on a burning car, which soon exploded. A Soviet torpedo bomber fell into the sea: the entire crew was posthumously awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union. Similarly, on December 22, 1944, V.P. Nosov’s plane from the 51st regiment was set on fire while approaching a German ship: the heroes went to ram...

Airborne mines and large-caliber bombs could also be hung on torpedo bridges. In this way, in July 1944, the A-20G was delivered from the air to the mouth of the Daugava and in the Gulf of Tallinn 135 mines, mostly magnetic, of the AMG type. The A-20G took two such mines weighing 500 kg each. The same mine laying was carried out, for example, near Koenigsberg. On an external sling it was possible to carry one FAB-500 bomb on each side or even a FAB-1000, but the latter option was used quite rarely. The targets for naval Boston Boston bombs were usually ships and port facilities. Thus, in August 1944, A-20Gs from the 2nd Guards Mine and Torpedo Division took part in a raid on Constanta. The strike group consisted of 60 Pe-2s and 20 A-20Gs. As a result, a destroyer, a tanker, and two submarines, five torpedo boats, a destroyer, an auxiliary cruiser, three more submarines, a transport and a floating dock were damaged, a fuel and lubricants warehouse was blown up, and repair shops were destroyed. In June of the same year, North Sea pilots carried out a similar combined strike on the port of Kirkenes. Il-2, A-20G and Pe-3 and Kittyhawk fighter-bombers operated together there. We also had to bomb minefields and anti-submarine networks.

The torpedo bombers of the 1st Guards Regiment were equipped with the first Soviet airborne locators designed to detect sea surface targets, such as the Gneiss-2M. At the suggestion of A. A. Bubnov, senior radar engineer of the Baltic Fleet Air Force, radars received from fleet warehouses were installed on five vehicles. First they were tested on Ladoga: the shore was discovered 90 km away, and a barge with a tug - 20.

The first combat flight was made on October 15, 1944 by regiment commander Hero of the Soviet Union I. I. Borzov. In conditions of poor visibility, the radar made it possible to find a group of three German ships in the Gulf of Riga. Aiming at the radar screen, the crew fired a torpedo and sank a transport with a displacement of 15,000 tons, loaded with military equipment. Subsequently, several more ships were sunk in this manner.

At sea, the Bostons hunted not only surface ships, but also for submarines. For example, on March 22, 1945, two A-20Gs sank a German submarine. Hero of the Soviet Union E.I. Frantsev even had two submarines - he destroyed one on January 21, 1944, and the other on April 4 of the same year. The methods were different: A.V. Presnyakov managed to sink the boat on the surface with a torpedo, and I. Sachko - with a bomb from a top-mast approach.

The latter method (dropping bombs near the surface of the water and then ricocheting into the side) was used by the A-20G, perhaps more often than torpedo throwing. From a distance of 5 - 7 km, the plane began to accelerate, then opened cannon and machine-gun fire to weaken the anti-aircraft gunners' resistance. The drop was carried out only 200 - 250 m from the target. This technique was also used by American pilots in the Pacific, but there they usually struck with bombs of relatively small calibers - up to 227 kg.

Probably the most famous example of successful actions of Soviet top-mast carriers is the sinking of the German air defense cruiser Niobe. On July 8, 1944, it stood in the Finnish port of Kotka. A regiment of dive bombers and two pairs of A-20G topmasts from the 1st Guards Mine and Torpedo Regiment took part in the raid. Each of the Bostons carried two FAB-1000 bombs. The dive bombers were the first to attack: two bombs hit the cruiser. Then the first pair of thousand-kilogram A-20Gs came in and crashed into the Niobe, and it sank. The second pair turned towards a nearby vehicle and hit it. In addition to "Niobe" the Baltic topmast carriers also have - battlecruisers"Schlesien" and "Prinz Eugen", auxiliary cruiser "Orion", many destroyers and transports.

Often top-mast carriers operated together with torpedo bombers. So, in February 1945, 14 A-20Gs from the 8th Mine and Torpedo Division north of the Hel Spit attacked a German convoy. They sank four transports and a minesweeper with bombs and torpedoes. Such interaction took place not only in large groups, but also during “free hunting” in pairs. For example, on February 17, 1945, a topmast-torpedo bomber pair, led by Captain A.E. Scriabin, launched an 8,000-ton transport and a patrol boat to the bottom of the Danzig Bay. There is even a known case of a topmast strike on a target on land. In June 1944, before the offensive of the Soviet troops, it was necessary to destroy the dam on the river located in the German rear. Svir. Through the joint efforts of A-20G topmasts, Il-4s with sea mines and attack aircraft suppressing anti-aircraft weapons, it was blown up.

The last bombs of World War II were apparently dropped by five A-20Gs of the 36th Torpedo Regiment on August 18, 1945, destroying railway bridge in Korea.

Our Bostons lasted longer in service than in the USA and Great Britain. Total for 1942 - 1945 Navy aviation received 656 foreign torpedo bombers, which by the end of the war made up 68 percent of mine-torpedo aircraft. If we discard the 19 English Hampdens, then everything else is Bostons of various modifications.

After the end of the campaign Far East naval aviation units continued to replace the Il-4 with the A-20. So, in the fall of 1945, the 2nd MTA in Kamchatka was rearmed. In the immediate post-war years, the A-20G was undoubtedly the main type of torpedo bomber in all navies.

A-20Gs were seen in the Baltic back in the 1950s. The 9th Guards Regiment in the North, already flying Tu-14 jets, retained a mothballed set of Bostons until 1954.

One Boston, recovered from the bottom of the sea, is in the Northern Fleet Air Force Museum: unfortunately, it has not been restored.

For Soviet pilots, the Boston remained in the memory as one of the best aircraft supplied to us by the Allies during the war.

The 7B and DB-7 prototypes did not have camouflage. They remained the color of polished duralumin. The surface of the aircraft was covered only with a protective colorless varnish.

The first A-20s that entered combat units were still pre-production vehicles, and for this reason also did not have camouflage. Identification marks were depicted directly on the shiny duralumin of the skin. But soon the planes received standard camouflage. The upper side of the aircraft was painted Olive Drab and the lower side was painted Neutral Gray. There are at least three shades of Olive Drab and two shades of Neutral Gray. These paints were: OD 35, which was similar to the French khaki of the First World War, OD 41 (dark) and OD 31 (higher green pigment), NG 33 (lighter) and NG 43 (noticeably darker) . Therefore, different copies of the A-20 could differ noticeably from each other in color. In 1940, a small series of "Douglas" received two-color camouflage OD 41/OD 35 on the upper side and sides. In July 1941, Olive Drab 41 and Neutral Gray 43 paints were left as the only samples. Color standards were sent to all aviation companies. The A-20A, B and C aircraft received this unified camouflage.

"Bostons" operating in North Africa, received desert camouflage. Irregular spots of Sand 26 were applied to the base OD 41 background. This was a sandy paint with a noticeable pink tint. Therefore, in many publications there is a misconception that the Americans painted their planes “pink.”

The aircraft's camouflage changed in 1943, simultaneously with the start of serial production of the A-20G modification. The base was still the OD/NG camouflage, but a third color was added - green (Medium Green 42 or Dark Green 30) - which was applied in the form of wavy spots on the upper side of the wings and horizontal stabilizers along the leading and trailing edges, and also sometimes on the top side of the engine nacelles. Sometimes the spots extended onto the fuselage in the area of the gunner's cockpit. Airplanes flying at night had their bottoms painted black instead of Neutral Gray.

The P-70 Nighthawk night fighters were painted entirely black (Black 44). Matte paint was usually used, but shiny paint was also available. A few vehicles wore Dark Olive/Black camouflage.

The French received DB-7s unpainted. Camouflage was already applied to aircraft in Casablanca. The French Air Force used two camouflage schemes: European and desert. The European or continental scheme consisted of patches of Khaki (similar to the British Dark Green), Brun Fonce (brown) and Gris Bleu Fonce (globular). The underside of the aircraft was painted Gris Bleu Clair (light grey-blue). In the desert scheme, Gris Blue Fonce was replaced by Terre de Sienne (sand) or Brun Fonce was replaced by Ocher (light ochre).

In the Royal Air Force, Havok and Bristol aircraft could wear several types of camouflage, depending on their purpose and theater of operations. Day bombers had the standard English camouflage of Dark Green/Dark Earth on the upper side and Sky on the lower side. Instead of Sky, night planes had their bottoms painted with black paint (Black).

Night fighters "Turbinlight" and "Intruders" were entirely painted with matte black paint. But there were also exceptions. In 23 Squadron, one of the Havocs carried a non-standard Extra Dark Sea Gray/Dark Green camouflage on the upper half of the fuselage. The only "Polish" Turbinlight from 307 Squadron was painted entirely in Medium Sea Gray with dark green spots applied over it. The aircraft probably received this camouflage already in the squadron.

"Douglas" of the Royal and South African Air Forces, operating in North Africa in 1942/43, wore the standard English desert camouflage: Dark Earth, Middle Stone spots, Azure Blue bottom.

Some of the Boston IIIs, which arrived in the winter of 1943/44, wore the original American Olive Drab/Neutral Gray camouflage.

But the later Bostons IV and V were painted according to the standards adopted at the end of the war. The entire aircraft (including the entire fuselage and the upper side of the wings) was painted British Olive Green (slightly lighter than Dark Green with a slight shade of gray), and the lower wings and stabilizers were painted in gray(Neutral Gray or Light Sea Gray). Part of the rudder was painted with British Medium Green paint, which was similar in shade to similar American-made paint.

The vehicles of the Australian 22nd squadron of the first series had English camouflage. Later, the planes were repainted using Australian paints: the sides and tops were Foliage Green (FS 34092) and Dark Earth (much darker than the English counterpart) or Light Earth (corresponding in shade to the English Dark Earth), and the bottoms were Sky Blue ( almost like English, but a little darker) or Light Slate Gray (similar to English). The A-20G aircraft that the squadron received later were painted Foliage Green.

Bostons of various series delivered to the Soviet Union most often had the original Olive Drab/Neutral Gray or Dark Green/Dark Earth/Light Sea Gray camouflage. In the Soviet Union, some cars were repainted. For example, the A-20G (43-10067, "Tallinn IAP") had camouflage complemented by dark green (possibly black) spots. Airplanes that had windows built into their blind noses, the nose segment was noticeably darker than the rest of the plane.

In winter conditions, many aircraft were coated with lime or washable white paint. The white color peeled off over time, so by spring the dark camouflage was clearly visible from under the white.

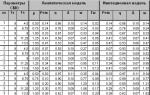

TTX modifications of the A-20

| Options | DB-7 Boston I | DB-7 Havoc INF | DB-7A Boston II (Havoc II) | DB-7B Boston III | Boston III Soviet | A-20B | A-20G-20 | A-20G-45 | A-20J | P-70 |

| span [m] | 18,67 | 18,67 | 18.67 | 18.69 | 18.69 | 18,59 | 18,69 | 18,69 | 18,69 | 18,67 |

| length [m] | 14,32 | 14,32 | 14,32 | 14,42 | 14,42 | 14.42 | 14,63 | 14,63 | 14,81 | 14,52 |

| height [m] | 4.83 | 4.83 | 4.83 | 4,83 | 4,63 | 483 | 4,83 | 4.83 | 4,83 | 4.83 |

| wing area | 43.17 | 43,17 | 43.17 | 43,20 | 43,20 | 43,20 | 43,20 | 43,20 | 43,20 | 43.17 |

| empty mass | 5160 | 5171 | 6150 (6203) | 7050 | 7060 | 6700 | 7700 | 8029 | 7770 | 7272 |

| a lot of norms. | 7250 | 7560 | 11000 | 11794 | 11350 | 9518 | ||||

| weight max. | 7710 | 8637 | (8764) | 9507 | 9735 | 9950 | 13608 | 12900 | 9645 | |

| maximum speed/0 m | 486 | 490 | ||||||||

| speed max | 501 | 475 | 516520) | 530 | 520 | 560 | 532 | 510 | 510 | 529 |

| at height [t] | 4563 | 3982 | 3050 | 3050 | 3050 | 3050 | 3050 | 3050 | 3050 | 3982 |

| cruising speed, | 431 | 443 | 435 | |||||||

| rate of climb | 12.4 | 12.3 | 6.8 | |||||||

| climb time | 8 | 10 | 10,4 | 10,4 | 5 | 8.8 | 7,5 (20,1) | 8 | ||

| height [t] | 3658 | 7380 | 5000 | 5000 | 3050 | 6100 | 3050 (6100) | 3050 | ||

| ceiling [t] | 8750 | 7864 | 8437 | 8800 | 8800 | 8650 | 7200 | 7230 | 7050 | 8611 |

| range | 1000 | 1603 | 789 | 1200 | 1200 | 1320 | 1740 | 1610* | 1810* | 1700–2350 |

| 3380** | 3380** | |||||||||

| * - with 900 kg bombs | ||||||||||

| ** - max. | ||||||||||

Technical description of the Douglas DB-7 Boston III aircraft, as well as the A-20G-20/G-45

The Douglas DB-7B was an all-metal, three- or four-seat, twin-engine light attack bomber. The aircraft was designed according to a mid-plane design, had an enclosed cockpit and a retractable three-post landing gear with a nose gear.

In March 1936, Jack Northrop and Ed Heinsmann began work on a project called the Model 7. It was supposed to create a three-seat all-metal upper wing, equipped with two Pratt & Untney R-985 Wasp-Junior radial engines with a power of 425 hp / 315 kW. The aircraft's armament consisted of movable and fixed rifle (7.62 mm) machine guns. Fixed machine guns were fixed in the forward part of the fuselage, and movable ones were mounted on the upper side of the fuselage. The aircraft was supposed to be produced in two versions: bomber-attack and reconnaissance. The weight of the aircraft reached 4500 kg. In the bomber version, the central part of the fuselage was occupied by a spacious bomb bay, which could hold 310 kg of bombs (40 bombs of 7.7 kg each). In the reconnaissance version, the lower side of the forward fuselage was glazed, opening up visibility for the observer and photographic equipment. The estimated speed of the aircraft was 402 km/h. which was not bad at that time.

Technical description of the Douglas DB-7 Boston III aircraft, as well as the A-20G-20/G-45

The Douglas DB-7B was an all-metal, three- or four-seat, twin-engine light attack bomber. The aircraft was designed according to a mid-plane design, had an enclosed cockpit and a retractable three-post landing gear with a nose gear.

Fuselage with working skin, reinforced with frames and stringers. The cross section is variable and has the shape of an oval. The crew seats were covered by armor with a total mass of 183 kg. Inside, the fuselage was divided into five parts, separated by four bulkheads. The bombardier's position was located in the bow; a hatch located at the bottom of the segment led into the compartment. The bow was well glazed, and from the bombardier's position there was an excellent view forward and to the side. The bombardier's position was equipped with a Pioneer radio compass and a Wimperis bomber sight. Next came the pilot's cabin, covered with a plexiglass canopy. The upper part of the lantern was a manhole cover that opened to the right. The pilot's seat was equipped with a full set of controls (including a control stick with a steering wheel) and control devices. The pilot's seat was adapted for a parachute seat. The pilot had no direct contact with the rest of the crew (as well as with each other), so all communication was provided by the RC-36 intercom and mechanical mail with pull rods.

The third fuselage segment contained a bomb bay with four locks. The bomb hatch doors were double-leaf and opened hydraulically. The positions of the gunner-radio operator and the lower gunner were in the fourth segment. The top of the gunner's cabin was covered by a double-leaf canopy. The rear door moved under the front door, revealing the machine guns. The bottom gunner could fire a machine gun through a double-leaf hatch in the bottom of the fuselage. The side view was opened by two rectangular windows on the sides of the fuselage. There was a hatch in the bottom through which both shooters took their places. There were several steps behind the trailing edge of the left wing, making it easier for the pilot to gain access to the cockpit. There was a path along the upper side of the wing near the fuselage along which the pilot walked to the cockpit. The bottom step was retracted during the flight. The last, fifth segment of the fuselage was the tail.

On the A-20G-20 aircraft, the nose did not have glazing. Instead of a bombardier, a battery of heavy machine guns along with ammunition was placed in the bow segment. Accordingly, the crew was reduced to three people. The top gunner's position was completely redesigned, replacing the double-leaf canopy with a rotating Martin-type turret. The fuselage in the turret area was expanded by 15 cm.

The wing is trapezoidal in shape, with working skin. The wing structure consisted of a main spar, two auxiliary spars in the center section and one in the engine nacelle area, as well as ribs. At the base the wing had a NACA 23018 profile, and at the tips - NACA 23010. The wing was equipped with flaps and ailerons with trim tabs. The ailerons are made of metal, but the covering is made of impregnated fabric.

The tail is classic, trapezoidal in shape with rounded tips. It consisted of a fin with a rudder and a horizontal stabilizer with an elevator. The stabilizers had a cantilever design, and the rudders were equipped with trimmers. The horizontal stabilizer had an elevation of 10?. The elevator is covered with impregnated fabric.

The landing gear is three-post with a nose strut. The racks are equipped with hydropneumatic shock absorbers and single wheels. The front wheel could rotate 360 degrees around the stand, which made taxiing easier. In addition, the front strut was equipped with a lateral vibration damper. The main landing gear wheels were equipped with hydraulic brakes. In addition to service brakes, there was a parking brake. All three wheels were retracted in flight, folding in the rear direction. The front strut went into a niche under the fuselage, and the main struts went into a niche under the engine nacelles. The main landing gear release system is hydraulic, the emergency system is pneumatic. The position of the landing gear was shown by a pointer on the dashboard (red light - landing gear retracted, green light - landing gear extended). Additionally, there was an audible signal that would sound if the throttle was less than a quarter open and the landing gear was not yet extended or locked.

The propulsion system consisted of two 14-cylinder air-cooled twin-star Wright-Cyclone R-2600-A5B engines. Takeoff power 1600 hp/1176 kW at 2400 rpm. The engines were equipped with a two-stage supercharging and rotated three-blade metal variable-pitch Hamilton Standard Hydromatic propellers with a diameter of 3.43 m. Additionally, the engines were equipped with an Eclipse electric inertia starter. It was possible to start the engines manually. The engines were equipped with Bendix-Stromberg RT-13-E-2 carburetors. The circulation of cooling air was provided by fixed reflectors and two sections of openable valves. The upper section served to cool the engine on the ground, the lower - in flight. In winter, the front opening in the engine nacelles was covered with shutters, preventing rapid cooling of the engine.

The A-20G aircraft was equipped with R-2600-23 engines with a starting power of 1624 HP/1194 kW, a maximum power of 1700 HP/1250 kW, an operating power of 1370 HP/1007 kW at an altitude of 1525 m, 1421 l .hp/1045 kW at an altitude of 3050 m and 1293 hp/951 kW at an altitude of 3505 m.

The fuel system consisted of four tested gas tanks located in the center section with a total capacity of 1464 liters. Two internal tanks held 500 liters each, two external tanks each held 232 liters. Each engine was connected to its own pair of tanks, although it was possible to redistribute fuel in the event of an accident. Aviation gasoline 2B-78 or 2B-74 octane number 90 was in tanks under a pressure of 0.09-0.1 MPa at altitudes up to 7850 m. In case of failure of the electric pump, an emergency manual fuel pump could be used. Inside the bomb bay, it was possible to mount three additional gas tanks with a total capacity of 1230 liters. These tanks served the left engine pumps. For flights at extreme distances, another gas tank was suspended under the bomb bay, which had a streamlined shape and could hold 1420 liters. This engine was connected to the pumps of the right engine. Fuel consumption when the engines were running on a rich mixture was 1204 l/h, and on a lean mixture - 341–478 l/h.

The lubrication system is individual for each engine. It consisted of two oil tanks with a volume of 71 liters, located in the center section, oil coolers installed on the internal (relative to the fuselage) walls of the engine nacelles, as well as a device for diluting oil with gasoline for starting engines in cold weather. In summer, MS or MK type oil was used, and in winter, MZS or DTD-109. The lubrication system operated under a pressure of 0.5–0.6 MPa, the minimum permissible pressure was 0.27 MPa.

The hydraulic system consisted of a tank, two pumps, a pressure accumulator, valves, pipelines, an emergency hand pump and pressure separators. The hydraulic system operated the mechanism for retracting and releasing the landing gear, flaps, brakes, the mechanism for opening and closing the bomb bay flaps, the mechanism for controlling the engine cooling system shutters, as well as the oil cooler flaps.

The pneumatic system duplicated the operation of the hydraulic system in case of failure of the latter. The system included a compressed air cylinder, bypass valves, air ducts and a main valve located in the cockpit.